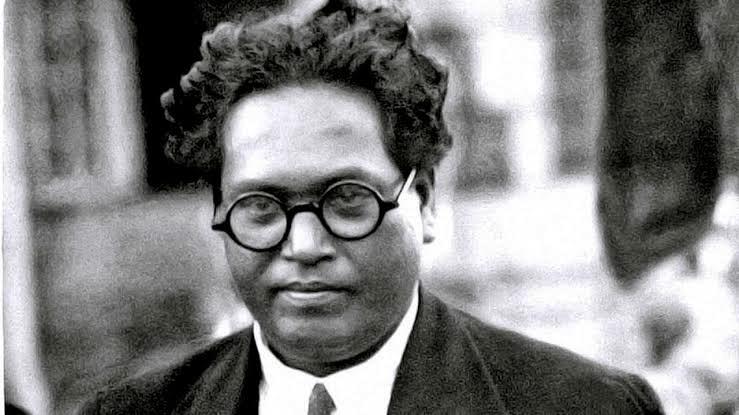

Dr. B. R. Ambedkar: The True Feminist of India

Author: Sandhya Bharti

Dr. Bhimrao Ambedkar was a feminist at heart. when we talk about feminist icons in india we often tend to overlook Dr Ambedkar while baba sahab’s work is most often cited as an example while opposing and fighting the caste system and caste bias we often fail to recognize the other aspects of his work in this feminist archive in this paper take a deep dive into Dr Ambedkar’s contribution to the feminist movement in India. It would draw attention to and examine how women have been treated in society from antiquity to the present. Women’s empowerment is the process through which they receive a larger proportion of resources, wealth, knowledge, and decision-making authority in society. In patriarchal Indian society, women have been oppressed and subjugated by men for all of recorded time. The Dalit community has long regarded him as their saviour. Dr. B. R. Ambedkar spearheaded the Hindu Code Bill, which marked a significant milestone in acknowledging women as equal citizens with inherent rights also discussed in this paper. This was a shift from the subcontinental Indian conception of women’s rights. It limited the factors that made up the “brahmanical patriarchy,” such as the lack of women’s property rights, endogamy enforced by religion, and marriages decided by caste. The primary reason behind his rejection of Brahmanism was the treatment of women, who were viewed as objects of amusement and placed at the bottom of mankind. His unwavering commitment to achieving women’s equality is admirable and praiseworthy. The first section of the presentation addresses Ambedkar’s Advocacy and Constructive reforms to Improve the Status of Women. The literary contributions made by Ambedkar and the historical challenges that women have faced throughout history. Social, political, and economic equality for women was something that Dr. Ambedkar firmly believed in. By highlighting the connections between gender inequality and caste, his books, talks, and other works offer a theoretical foundation for comprehending caste-based violence against women. The contribution of Ambedkar to improving the status of women in Indian society is also covered in this essay.

In the modern era, when caste-based violence against women is on the rise and numerous academicians and social groups are working to expose the layers of discrimination faced by women because of their caste-based identity, Dr. Ambedkar’s ideas are highly relevant and should be emphasised as one of the prominent and nuanced arguments highlighting the plight of women facing multiple oppressions of caste, class, and gender. For the most part, the feminist movement has ignored the voices of marginalised groups and portrayed them as part of the common mainstream without providing adequate space for their diverse challenges. Women now have liberty, equality, and fairness in life as a consequence of his vision and accomplishments. Because of this, women in contemporary India now play an equal role in contributing to overall growth. His contributions give women the willpower to combat social injustice and the law, giving them hope for equality and a life of dignity.

Keywords– Ambedkar, Hindu Code Bill, Feminism, Caste, Gender, Indian women, women empowerment, Social justice, Equality.

Introduction: Dr. B. R. Ambedkar: The True Feminist of India

Feminism has played a significant role in drawing attention to the disparate socialisation that women experience throughout the years. Numerous public mechanisms are in place that prohibit women from participating in society and from being included, therefore marginalising half of the population. Since its origin, the feminist movement has experienced numerous significant transformations and the last three decades have given birth to growing exposure of third world female movements. Dalit feminism in India takes aim at gender and caste from two different angles. No kind of oppression ever occurs in isolation and thus, when it pertains to the subjugation of Dalit women, one has to take into consideration their caste as well as their gender. Protest movements that aimed to improve Dalit women’s social, economic, and political circumstances emerged in the first few decades of the 20th century. These groups emphasised that women’s oppression was primarily fueled by the interconnection between industrialization, colonialism, and the commodity of the female body. While reading BR Ambedkar, one cannot skip the profound insights Babasaheb had on social issues relevant to his times.

Dr. B. R. Ambedkar (1891–1956) was not only a social reformer, statesman, and Indian lawmaker who fought for the rights of upliftment of the Dalits and the socially backward class of India but also a great feminist of India. One of the nation’s early feminist leaders and supporters of women’s rights is Babasaheb Ambedkar. Liberal feminists greatly respect Dr. B.R. Ambedkar for his support of Indian women’s rights within the Indian social structure. Babasaheb fought tirelessly to transform the situation of Indian women and grant them legal and constitutional rights to freedom, equality, and individuality. ‘Just ask an educated liberal woman of India how they got their rights, irrespective of caste and creed’(Elancheran, 2018). Perhaps no other reformer or statesman has done as much. In our society, the most pervasive and profound kind of oppression is that which targets women. Because they have a close experience with the politics of oppression and repression, women have been subjected to the status of the other, marginalised, or colonised throughout history. They are also referred to as subalterns due to their lower social status (together with Dalits). Ambedkar’s profound comprehension of the social and economic stigmas that affect Indian society helped him rise to prominence. He was aware of the suffering and misery endured by the oppressed groups. He advocated growth and education as remedies for the atrocities of caste. Ambedkar was adamantly against the caste system in India, which is the foundation of the Hindu social structure. He criticised the Brahministic belief that women belong at the bottom of the social hierarchy. He also challenged Manusmriti and questioned Manu’s religious beliefs and goals, which justify denying people their freedom, self-respect, and entitlement to an education and discovered that the principles of equality, self-respect, and freedom for all form the foundation of Buddhist doctrine.

Ambedkar, who served as the first law minister of independent India, crafted the landmark Hindu Code Bill, which guaranteed gender equality in laws primarily dealing with marriage and inheritance. This bill struck at the core of the “graded-inequality” inherent in the Hindu caste system. He envisioned a number of measures, including giving women the same rights as men and treating them as equals: “one change is that, the widow, the daughter, and the widow of the predeceased-son; all are given the same rank as the son in the matter of inheritance.” A portion of her father’s estate is also granted to the daughter, which is equal to half of the son’s share.[1] Ambedkar proposed the interwovenness of gender and caste when describing the disadvantaged status and dilemma of Indian women. Endogamy is a prerequisite that has a significant impact on women in order to preserve the caste system.

“Many women become invalid for life and some even lose their lives by the birth of children in their deceased condition or in too rapid succession. Birth control is the only sovereign specific remedy that can do away with such calamities. Whenever a woman is disinclined to bear a child for any reason whatsoever, she must be in a position to prevent conception and bring forth progeny which should entirely be dependent on the choice of women.” — Dr. B R Ambedkar

Ambedkar has underlined the need to grant women’s rights and equality to all segments of society. Maintaining their modesty and dignity is our duty (Shukla, 2011). He also supports movements that have been spearheaded by female leaders. It is his belief that women of all backgrounds should be given confidence and given the opportunity to make meaningful contributions to socio-cultural changes. Additionally, he is in favour of movements led by women. He thinks that women from all walks of life ought to be empowered and given the chance to significantly impact societal and cultural shifts. Since he thought that social justice could only be achieved within a contemporary institutional framework, his approach to women’s liberation was liberal and progressive. He so championed the ethos of constitutionalism that guaranteed women’s equality and dignity.

He was adamant about women’s roles and emphasised the need for them to work alongside his husband. However, she does not labour for him as a slave. She must refuse to be a slave and maintain her dignity. Additionally, he thinks that if all women embrace this reality, they would undoubtedly win the respect of society at large and be able to reclaim their own identities. Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar put up a valiant fight to protect women’s social and economic rights. He emphasised how crucial it is to uphold women’s modesty and preserve their sense of dignity. He studied the Hindu Shastras and Smritis extensively in an attempt to understand why women in India were treated so poorly. He began his efforts in 1920 and used the renowned periodicals Mook Nayak and Bahishkrit Bharat to address issues of social order and system within the Hindu community in 1920 and 1927, respectively.

Ambedkar’s Advocacy and Constructive reforms to Improve the Status of Women

The well-known periodicals Mook Nayak and Bahishkrit Bharat, written by Ambedkar, served as platforms for voicing opposition to gender discrimination and the necessity of women’s rights. Under the auspices of Ambedkar, women’s movements went through three phases: in the 1920s, they joined men in movements like the temple entry movements; in the 1930s, they established independent organisations; and in the 1940s, they organised politically under the All India Depressed Classes Mahila Federation. Twenty-five thousand women attended its 1942 Nagpur congress (Dhara, 2016). His ideas and words had a significant impact on women. The launching of the ‘Mahad Satyagraha’ in 1927, a bonfire of Manusmriti in 1927,6 the Kalaram Temple Entry Satyagraha in 1930 and formation of women’s association in 1928 in Bombay were positive steps to organise and empower women so than they could fight to reclaim their social rights (Singariya, 2014, p. 2). He was effective in transforming their way of life significantly. He desired a lavish lifestyle for them. He thus demanded that they refrain from donning attire or accessories that would beg for sympathy. Women’s involvement in the movement was initiated by Dr. Ambedkar. Given the challenges of raising children, he counselled women to focus on other activities and avoid having several children (Dhara, 2016).

Those who fought for the development of the disadvantaged and the abolition of caste systems, he recognized, could not have accomplished this without the women’s own liberation. He rallied women and called them to engage in the campaign against caste stereotypes, caste discrimination and lastly against the overall caste system. That is why, in addition to taking part in the Mahad Tank Struggle, women also marched in the parade with males. Women should organise themselves, he advised. He expressed his admiration for the sizable number of women present at the Nagpur women’s conference on July 20, 1942, and advised them to be progressive by eliminating customs, rituals, and traditionalism, as these things hindered their advancement. Moreover, he emphasised the value of education and its involvement in empowering people generally and women specifically. Encouraging and strengthening people’s abilities to integrate into mainstream society is the broad definition of empowerment. The only path from oppression to democratic engagement and participation is via education. It is an effective instrument for community and individual empowerment. Indian society has always excluded some sections of the population from educational possibilities. Therefore, among other oppressed groups, particularly women, a lack of knowledge contributed to a number of issues. Dr. Ambedkar devoted all his endeavours to ensure the educational possibilities without any type of prejudice to all the residents of India. Every segment of society has been excluded from educational possibilities by society. He urged people to break free from antiquated practices, rituals, and superstitions by doing away with all traditionalism, embracing contemporary ideals, and cultivating a progressive worldview. In the process of annihilating the caste, he also incorporated them (Bakshi, 2017).

Dr. Ambedkar, who firmly believed in the power of women, stated:

“I measure the progress of a community by the degree of progress which women have achieved. Let every girl who marries stand by her husband, claim to be her husband’s friend and equal and refuse to be his slave. I am sure if you follow this advice, you will bring honour and glory to your shelves.”(Singariya, 2014, p. 2)

He urged women to take charge of their own organisation. When he addressed the women’s conference in Nagpur on July 20, 1942, he was struck by the sizable number of women in attendance. Dr. Ambedkar stated that women held the key to progress during the All India Depressed Classes Women’s Conference, held on July 20, 1940, in Nagpur. He said, “I’m a big fan of the Ladies’ Association.” I am aware that how they could operate relies on the public’s attitude and their susceptibility to persuasion. It is their duty to instil in their children a strong sense of ambition. During the Round Table meeting, Ambedkar delivered a number of crucial remarks. He spoke out for Dominion Status and offered the disgruntled classes a voice. His speech was well received by the British public. He said that women should be progressive and concentrate on doing away with customs, rituals, and traditionalism because these things impeded their advancement. Sainik Dal was founded by women. Rahabhai Vadale, who was inspired by Ambedkar to give women confidence, spoke out against all forms of exploitation and in favour of women’s rights during a press conference. The newspaper Chokhamela was founded by Tulsibhai Bansole. Ambedkar urged the Devadasi women—who are typically from Dalit and other oppressed castes—to abandon the retrogressive religious practice of offering prepubescent girls to deities in Hindu temples and become “sexually available for community members” in a speech he gave in 1936 to communities of Vaghyas, Devadasis, Joginis, and Aradhis in Kamathipura. He said: “You will ask me how to make your living. I am not going to tell you that. There are hundreds of ways of doing it. But I insist that you give up this degraded life… and do not live under conditions which inevitably drag you into prostitution..”. Under the impact of his teachings, David, a mediator for a brothel, quit his job. In addition, Ambedkar opposed the devdasi system, prostitution, and child marriage. (Singariya, 2014, p. 3) Although women had a very high standing in ancient India, their worth and prestige eventually diminished. Hence, women were forced to view themselves as nothing more than objects of passion and pleasure. Their unique personalities and basic human rights were taken away from them. The Bombay Legislative Council declared Dr. Ambedkar to be a designated individual on February 18, 1927. He made an effort to persuade Native Americans to fight for the British Government. His views on Birth Critical and the Maternity Benefit Bill made women more valuable in the eyes of the public. He was a fervent advocate for the Maternity Bill. He said, “It is a legitimate concern for the country that the mother should get a certain amount of rest during the prenatal period, and the Bill’s standard is based entirely on that principle.” “So, yes, Sir, I will agree that a lot of the weight of this should be carried by the government. I am willing to agree to this fact because the government’s main concern is to protect the people who get help from the government. Also, you’ll notice that the government has been accused of something different in each country when it comes to maternity benefits.” “Thus, certainly, Sir, I will concur that the government should bear the majority of the responsibility for this”. Subsequently, the Madras Legislative Council enacted the Maternity Benefit Act in 1934, and several other provinces followed suit. He successfully pushed for the nationwide adoption of the Mines Maternity Benefit Bill between 1942 and 1946. A national Maternity Benefit Act was approved by the federal government in 1961.

According to the Special Marriage Act, a marriage can only be deemed lawful if both partners are monogamous, of sound mind, of marriageable age, and not too closely related. Certain causes are exclusive to the wife in Hindu and civil marriages; for instance, section 313 criminalises abortions carried out under duress or without the agreement of the woman.Female members will have equal inheritance rights in heirs and property, according to a number of statutes, including the Hindu Succession Act and others. The fact that the aforementioned actions were carried out with Ambedkar’s assistance demonstrates his deep desire to empower and elevate women in society. The Hindu Code Bill, which was innovative in restricting women’s property rights, was proposed by Dr. Ambedkar in 1948, but the parliament rejected it. Despite his best efforts, he encountered several challenges along this march. His resignation as a cabinet minister in 1951 was stated in the answer. The twentieth century might be seen as the actual emancipation of women. Unity is meaningless without the accompaniment of women, according to Dr. Ambedkar, who had a strong concern for the welfare of women. Dr. Ambedkar believed that the caste system’s cruel traditions should not serve as the foundation of society, but rather objective principles.

Hindu Code Bill And Ambedkar

Women were first acknowledged as equal citizens with rights rooted in their uniqueness through the Hindu Code Bill, spearheaded by Dr. B. R. Ambedkar. This was a change from the perceptions of women’s rights in the Indian subcontinent. The restrictions placed by the religion on endogamy, caste-based marriages, and the denial of women’s property rights were among the components of the “brahmanical patriarchy.” This measure was introduced in parliament on August 1, 1946, however it was never further pursued. Dr. B. R. Ambedkar, the law minister, “brought it up again in the Constituent Assembly on April 11, 1947,” following India’s independence. The Hindu Code Bill demonstrates Ambedkar’s deep concern for women’s position. He has also remarked that the work he conducts on the Hindu Code Bill would be just as significant as the work he does on the Constitution.” [2]

Since religion served as the foundation for inequality in Indian culture, Ambedkar codified the personal law of Hinduism. The predominant caste groups portrayed Hinduism as a question of identity only, ignoring the reality that the fundamental tenets of both their caste and religious identities were based on the many subjugations of women. The bill itself was an immense exodus from Hinduism and its degrading set of laws regarding gender. Up to that point, “Hindu law” was also randomly interpreted through oral readings of various content from the Vedas, Smritis, and Puranas. In ancient legal texts like the Manusmriti, Arthashastra, and other Dharmashastras, women were not allowed to own property. In contrast, the Hindu Code Bill aimed to eradicate discrimination against women and provide them the freedom to own property. By putting out the theory that men and women should be treated equally in order for a society to advance, this measure cleared the path for the elimination of the “graded inequality” of the caste system. There is evidence that women without assets face violent threats and other forms of inequality in the home. The measure itself marked a dramatic break from Hinduism and the discriminatory practices it maintains against women. Because there were no true rules or cultural homogeneity, women’s lives were often placed in the hands of male Hindu interpreters. The Two distinct sets of rules applied to different aspects of Hinduism, including inheritance, marriage, adoption, and other matters. These legal codes were called Dayabhaga and Mitaksra. A person’s belongings do not exclusively belong to him, according to Mitakshara law. Rather, it’s seen as a component of his coparcenaries, which are his father, son, grandson, and great-grandson—a reference to his male lineage. This provides them with complete ownership of the asset from the time of their birth. In Dayabhaga, however, every single piece of property is held by a distinct person. This suggests that every person who inherits property from their parents is given total control over the acquired assets. This last set of legislation, which would become referred to as the Hindu Code, was incorporated into the bill by Ambedkar.

A Tool for Denying Property Rights: Caste

Studies in anthropology and sociology do demonstrate that gender inequality has been the fundamental component of all social, political, and cultural identities (Kamei, 2011, p. 55). Religious writings serve as the “ideological” and “moral” pedestal for women’s duties and position in Indian culture. The primary religion is Hinduism, and the caste system is central to this religion, which operates on the principles of contamination and purity. The “ideological” and “moral” pedestal for women’s duties and position in Indian culture is provided by religious literature. The main framework is Hinduism, and the core of Hinduism is the caste system, which operates on the principles of contamination and purity. In a caste-based system, endogamy—marrying within the caste circle only—has been enforced to maintain caste purity as women are viewed as the portals of caste due to their reproductive abilities. Men held women under their authority in order to carry it out. (Ambedkar, 2013, p. 10) such that they were unable to make judgments on their own in every area. But since caste rules are often broken, certain measures—like excommunication—were put in place to keep Hindus in the purity of caste. However, these systems also serve as patriarchal forms of discrimination, whereby a woman who marries a man from a lower caste than her own would be banished from her paternal varna and will also no longer be eligible for previous caste advantages. However, a man who marries a woman from a lower varna than himself will not be banished to a lower varna and will still be able to use his varna rights (Rege, 2013, pp. 169–178). The caste-based patriarchal structure in question prevented women from having an absolute right to land or other moveable or immovable property. This is because, in a patriarchal system, women are subservient to their husbands and their property may pass to other people after marriage, including men from different castes if they marry. Therefore, gender inequity is the fundamental principle of Indian society.

Hindu Code Bill: A Document of Women Rights

The Hindu Women’s Rights to Property Act, 1937 was passed during the British era, giving Hindu widows the first-ever right to inherit a portion of their husbands’ property and to specify how his undivided family estate would be divided (Banningan, 1952, p. 174). This marked the beginning of the era of women’s rights. However, this was only a limited interest, as on their death, the property would be inherited by their husband’s heirs. (Sinha, 2007, p. 51). The B. N. Rau Committee was appointed by the British government in 1941 to investigate the state of women’s property rights throughout the subcontinent, and this law came after. Two measures, the Hindu Marriage Bill and the Intestate Succession Bill, were drafted by the Rau Committee. In 1943, they were proposed in the Central Legislature, but the conservative groups’ resistance forced them to be abandoned. Reorganising these legislation into a draft code (Ray, 1952, pp. 273–274), often referred to as the Hindu Code Bill (Som, 2008, p. 170), gave new life to the endeavour in 1944. Law Minister Ambedkar submitted the Hindu Code Bill in the Constituent Assembly on April 11, 1947, after it had been tabled in Parliament in 1946 but had not been considered (Banningan, 1952, p. 174). The Hindu Code Bill mirrored Ambedkar’s concern for women’s position. In addition to dealing with maintenance, marriage and divorce, minorities and guardianship, and adoption, he clarified that the purpose of the measure was to clarify and amend Hindu law pertaining to seven distinct subjects of rights to property of deceased Hindus who died intestate or without making a will.

The measure broke with the demeaning rules against women found in Hinduism. Regarding inheritance, marriage, adoption, and other matters, Hinduism has two different kinds of rules. According to Halber and Jaishankar (2008)/2009, p. 675) they are Mitakhshara and Dayabhaga. A man’s property is defined under Mitakshara law as not a single item, but rather a shared or coparcenary ownership of male lineage, i.e., father, son, grandson, and great-grandson, only via birth. Property ownership has an individual character under the Dayabhaga body of law, meaning that a person who inherits property from their ancestors has full ownership rights over it. This last legal thread was included by Ambedkar in the Hindu Code Bill, which aimed to establish common law by adapting it to the requirements of the contemporary day (Ambedkar, 2014, p. 6). In terms of Hindu law, the lady received just a “life estate” upon inheriting property. With the exception of situations where it was required by law, she may keep the property’s revenue but not its corpus. It was necessary to transfer the property to the husband’s revisionists. In this aspect, the Bill changed two things. The limited estate was first transformed into absolute estate, much like their male counterparts. Second, it eliminated the revisionists’ posthumous rights to the property (Rege). The bill’s primary justification was to elevate everyone in the country, especially women. It aimed to concentrate on two primary goals: (a) improving women’s position and (b) getting rid of all differences and inequality. It aimed to outlaw polygamous unions and abolish the predominance of other marital structures. It aimed to make monogamous marriages the only ones that were legal and to end the popularity of other marriage systems (Katulkar, 2008). The legislation granted women rights to property and adoption, which Manu had previously denied them. Men and women were urged to be treated equally in legal situations. Dr. Ambedkar stated:

I should like to draw the attention of the house to one important fact. The great political philosopher Burke who wrote his great book against the French Revolution said that those who want to conserve must be ready to repair. And all I am asking this House is: if you want to maintain the Hindu system, Hindu culture and Hindu society do not hesitate to repair where repair is necessary. The bill asks for nothing more than to repair those parts of the Hindu system which have become dilapidated. (Singaria, 2014, p. 3)

Ambedkar considered sacramental marriages as against the spirit and philosophy of the Constitution that brings slavery to women (Katulkar, 2008). The Hindu Code Bill incorporated the following: (1) The right to property of a deceased Hindu who has died intestate without making a will, to both male and female. (2) the order of succession among the different heirs to property to a deceased dying (3) the law of maintenance (4) marriage (5) divorce (6) adaptation (7) minority & guardianship. (Kumar, 2016, p. 217)

Female heirs were discriminated against based on whether or not they were married and had children. Eliminating this prejudice was another goal of the Hindu Code Bill. Ambedkar gave equal standing to the widow of a deceased son, the widow of a daughter, and other widows. The daughter’s portion of her father’s and her husband’s property was specified as being equal to the son’s in order to reestablish gender balance. As an equal heir to the son, widow, predeceased son’s widow, predeceased son’s son, and predeceased son’s widow, she was granted equal recognition. Notably, Ambedkar established complete equality between a son and a daughter by declaring that “son also would get a share as equal to girl’s share in mother’s property, even in Stridhana (defined in Hindu Law as wealth received by women as gifts from relations) too.” Women were to be given complete property rights under the measure. Women’s rights under Dayabhaga law were limited to their “life estate,” or the property they could use and enjoy for the rest of their lives, without being able to sell it under any circumstances. Her husband’s family would inherit this land after her death, but Ambedkar also brought about a radical shift in this regard.

Because of his fervent belief in the principles of liberty, equality, fraternity, and dignity, Ambedkar was able to reinterpret the law. An egalitarian society would be restored if caste prohibitions on marriage and adoption were lifted, polygamy was outlawed, and monogamy was encouraged. Additionally, women’s full share of property ownership would be seamlessly integrated. This measure aimed to rebuild society around gender-neutral concepts. The bill aimed to create a society where all genders and castes would be treated equally, where men and women would be treated equally, and where everyone would enjoy a perfect kind of democracy and equality in society. In other words, it was a type of equaliser. Hence, the bill was against the structure of domination and oppression of women and, by way of this, challenged the very philosophy of Hinduism. Amidst strong opposition from Hindu Orthodoxy, especially from Hindu Mahasabha and Bharatiya Jana Sangh, which exalt the Manuwadi lineage, the Bill was withdrawn rather than accepted due to its drastic deviation from traditional Hindu philosophy. It has been said that the bill is against “Indian culture” because it allows for divorce and monogamy, which may prevent a man from having a son, making him sacrosanct for salvation, among other reasons. The Hindu Mahasabha opposed the bill in order to prevent any legislative intervention in religious matters pertaining to Hindus. The bill’s clauses regarding women’s property rights, monogamy, and divorce were strongly opposed by religious, conservative, and patriarchal social groups in the community.

Although Ambedkar saw the Hindu Code Bill as a chance to reform Hindu culture, his status as an untouchable posed obstacles to his efforts to change Hindu law. Despite this, he was a big champion of the bill and even chose it above his health. The fact that Jereshastri declared, in a lewd manner, “that Ganges water from a gutter cannot be considered holy,” makes this clear. A few MPs publicly proclaimed they would not allow the Bill to pass as long as Dr. Ambedkar was leading the charge. Even President Rajendra Prasad voiced strong opposition to the bill, saying that it “interferes in Hindus’ personal law and would satisfy only a few purported progressive people.” Deputy Speaker Ananthasayanam Aiyyangar was also against Ambedkar’s continued implementation. It had been harder for Ambedkar to manoeuvre because of his status as “a non-congressman.” A few MPs publicly proclaimed they would not allow the Bill to pass as long as Dr. Ambedkar was leading the charge. The Ram Rajya Parishad argued, “Under the Constitution every citizen has been assured of his or her religious freedom, but, in the name of reforms direct interference is being shown in religious matters of the Hindus by adopting such measures as the Hindu Code Bill … the Hindu Code Bill and such other measures as shall be in direct conflict with our Indian Culture, as well as with the duties towards the husband, on the part of women, shall be repealed, if enacted by the present government.” A slogan widely used against the bill was, “Brothers and sisters will be able to marry each other if the Hindu Code Bill becomes law!” Most Hindus consider that members of the same clan (Gotra) are related; male and female members of the same clan are therefore considered as brothers and sisters, even if the actual degree of relationship is remote ( Banningan, 1952). Misogynistic statements also marred the proceedings in the Constituent Assembly during this time. The then-President of India, Rajendra Prasad, contended that only “over-educated” women supported the bill and that his wife would never support the divorce provision (Constituent Assembly Debates, Vol. IV). Ambedkar rebelled against the status quo by resigning as law minister in order to advance women’s rights. This underscores the fact that gender justice has been an integral part of the political rhetoric against caste both historically and theoretically. This may be reviewed by examining the remarks made by Ambedkar upon his resignation in response to caste supremacists’ failure to pass the Bill. He wrote, “To leave inequality between class and class, between sex and sex which is the soul of Hindu society untouched and to go on passing legislation relating to economic problems is to make a farce of our Constitution and to build a palace on dung heap. This is the significance I attached to the Hindu Code.” ( BAWS, Vol. 14). The smooth enactment of this bill in 1955–1956—when Ambedkar was not serving in the cabinet—in four separate acts—the Hindu Marriage Act of 1955, the Hindu Succession Act of 1956, the Hindu Adoption and Maintenance Act of 1956, and the Hindu Minority and Guardianship Act of 1956—is evident.

The Hindu Code measure was supported by Sharmila Rege, who stated in Against the Madness of Manu: B. R. Ambedkar’s Writings on Brahmanical Patriarchy that Ambedkar acknowledged women as people and politically equal citizens on par with males through this measure. Rege pointed out that the purpose of this measure was to stop beliefs that perpetuate Brahmanical patriarchy, such as forced endogamy, the idea that women have no unqualified right to own property, and the idea that marriage is indissoluble for women. Ambedkar’s love for the liberal ideas of liberty, equality, fraternity, and dignity, she said, helped him recast the law.

Ambedkar’s literary contribution to women’s rights

The Indian social structure, Hindu culture, and caste system have all been criticised by Bhim Rao Ambedkar. Other than his many remarks emphasising his fundamental conviction in women’s equality, A groundbreaking achievement was Ambedkar’s 1917 work, “Castes in India,” which theorised the relationship between caste and gender-based discrimination in India. Dr Ambedkar states that Caste in India means an artificial chopping off of the population into fixed and definite units, each one prevented from fusing into another through the custom of endogamy. Thus, for Dr Ambedkar, endogamy or absence or prohibition of intermarriage is the essence of the caste system. In the Indian context, Dr. Ambedkar discusses how certain methods of controlling women and their sexuality are contingent upon the upholding of the caste system. He illustrates this by demonstrating how measures such as child marriage and strict controls on widow remarriage were implemented in order to address the problematic notion of surplus women. In his work, Castes in India: its mechanism, inception, and evolution, Ambedkar produced a foundational work on how caste flourishes in India as part of his initial endeavour to comprehend the Indian social system. The realisation that endogamy between various social groupings in India is the primary factor sustaining the caste system has happened quickly. As Ambedkar envisioned, the corrupt and heinous Indian societal evils of forced widowhood and sati practice emerge from the interconnected systems of caste and endogamy. Even though these behaviours were outlawed in the early nineteenth century, not enough research has been done to determine the causes of India’s wicked social customs. The subjugation of Indian women through the imposition of strict endogamous statutes sanctioned by upper caste Indian society’s rules underpinned the reification of the caste structure, which Ambedkar investigated with unwavering scholarly assiduity (Ambedkar, Vol. 1, 2014). He posited a plausible, logical intervention and connected endogamy, girl-child marriage, enforced widowhood, and sati as the offshoots of preserving closed caste units. According to Ambedkar’s theory, the women within a caste group are crucial to the system’s significant operation. This means that it is essential that widowhood be handled in the event of an unplanned event by creating legal codifications supported by religious rituals (Ibid). He emphasised the difference between “surplus man” and “surplus woman”:

I am justified in holding that, whether regarded as ends or as means, Sati, enforced widowhood and girl marriage are customs that were primarily intended to solve the problem of the surplus man and surplus woman in a caste and to maintain its endogamy. Strict endogamy could not be preserved without these customs, while caste without endogamy is a fake…when I say origin of caste, I mean the origin of the mechanism of endogamy(Ambedkar, Vol 1, p 14).

Ambedkar also identified the point at which caste and gender interact and proposed a theory explaining how these two reinforce one another to uphold the status quo. The prevalent understanding of gender studies in India is based on the idea of Brahmanical patriarchy. Ambedkar made it quite evident that the hierarchical Hindu caste system’s grading system is the foundation for gender discrimination. He explained the vertical caste structure and how Hindu women at the bottom of the caste system are increasingly affected by patriarchy.It is possible that he was the first Indian reformer and scholar to hypothesise about how Dalit women are affected by multi-layered patriarchy. According to his theory, the lowest place in the vertically arranged caste system, which is based on the superimposition of compulsive endogamy over exogamy, is occupied by Dalit women. Ambedkar recognized that women’s participation in the conversation to alter their subordinate situation was necessary. Without women’s participation, the notion of releasing women to eradicate gender inequity would remain an unfinished undertaking. He wanted Dalit women to be as independent as those from higher castes. As a result, the Ambedkarite teaching imparted during the Dalit Mahila Parishads (Dalit women’s conferences) related to all types of women. He remarked: (Ambedkar, 2014, Vol. 17, Part 3, pp. 282-83):

I made it a point to carry women along with men. That is why you will see that our [c]conferences are always mixed [c]conferences. I measure the progress of a community by the degree of progress which women have achieved…learn to be clean: keep free from all vices. Give education to your children. Instil ambition in them. Inculcate in their minds that they are destined to be great. Remove from them all inferiority complexes. Don’t be in a hurry to marry: marriage is a liability. You should not impose it on your children unless financially they are able to meet the liabilities arising from marriage. Those who marry bear in mind that to have too many children is a crime. That parental duty lies in giving each child a better start than its parents had. Above all, let each girl who marries stand up to her husband, claim to be her husband’s friend and equal, and refuse to be his slave. I am sure if you follow this advice you will bring honour and glory to yourself.

Such statements at women’s conferences demonstrated Ambedkar’s mettle and support for women’s rights, which holds that everyone should have equal possibilities for freedom. Ambedkar conducted substantial theoretical work on women’s roles in Indian society, in addition to spearheading several political and social initiatives aimed at ensuring equality for all.

Later on, in his article “The Rise and Fall of Hindu Women: Who was responsible for it?” Dr. Ambedkar went on to address the cause of women’s decline in Hindu culture. Through his literary creations, he disentangles the injustice and inequality that characterised the Hindu societal structure. After reading the Hindu shastras and smriti, Ambedkar came to the conclusion that these texts were a primary source of the injustice and subjugation experienced by women. In his well-known work, “The Rise and Fall of Hindu Women,” he examined in great depth the historical standing of women and how it contributed to their miserable situation in Indian culture. Ambedkar said that under the Brahmanical framework, women were accorded the same status as Shudras, despite the fact that these individuals were deprived of the fundamental human rights of possessing property, exercising self-respect, learning, and giving up, which is considered the “single path to salvation” in Hinduism. In his investigation, he came to believe that women had a very active role in the nation’s intellectual and social life during the Pre-Manu period, also known as the Aryan age. Additionally, it was discovered that women were expected to do Upanayanam, which may be inferred from the Atharva Veda, which states that a female has the right to discuss her own marriage after completing her Brahmacharya training. Women studied different shakhas of the Vedas and attended Gurukuls, according to Panini’s Ashtadhyayi. In a similar vein, Patanjali’s Maha Bhyasya demonstrated that women taught girls the Vedas and served as instructors. Women were afforded an equal standing with males and were allowed to voice their opinions on matters of religion, philosophy, and other significant subjects. Numerous tales, such as those of Janak and Sulabha, Yajnavalkya and Gargi, among others, demonstrate how honourable and deferential women were in those days.

He also showed disparate images of Buddhism and Hinduism and implied that women had a higher place in Buddhism. Women were excluded from all forms of knowledge under Hinduism. This he linked back to the Manusmriti, which forbids women from learning the Vedas, depriving them of equal standing even after death, when the final rituals, or sanskaras, are performed for women without the chanting of the Vedas. Similar to preceding Brahmanical writings, the Manusmriti precluded women from obtaining knowledge.This action was taken without any justification, which is one of the main reasons Hindu women have failed. He quotes Buddha, on the other hand, as granting women access to Parivraja, or travelling ascetic, through which they may acquire knowledge and achieve spiritual enlightenment. Buddha thereby altered the lives of women by freeing them from slavery. According to Manusmriti, Her father protects her in childhood, her husband protects her in youth, and her sons protect her in old age; a woman is never fit for independence. (law of manu, 2000) Dr. Ambedkar has challenged this, pointing out that women have been denied independence all of their lives. In addition, it is said that wives should revere their husbands regardless of whether they are “destitute or virtuous or seeking pleasure elsewhere, or devoid of good qualities”. According to Dr. Ambedkar, there is proof that women enjoyed a greater standing during the pre-Manu era, when they were men’s free and equal partners and had the flexibility to pursue their own interests, including economic independence, divorce, and remarriage. Buddhism, with its emphasis on equality, self-respect, and education, offers women liberation, in his view. Unlike Manu, he said, Buddha never attempted to denigrate women—instead treating them with love and respect. He imparted religious philosophy and the Dharma of the Buddha to women. Every man and woman is free in Buddhism, according to him. They are above priests and rituals, and any supra-natural agency. Between men and women, there is no such thing as inequality.

He believed that the only effective tool that would liberate all women from the chains and bonds of Indian culture was education. Education is the only thing that can give women a great degree of self-confidence and the power to resist all of their humiliations. Women were encouraged by Ambedkar to speak up bravely and leave their social circles during the Kalaram temple-entry struggle. Fifteen thousand individuals showed up to support this campaign in 1930. One of the ladies touched by Babasaheb’s message was Radhabai Vadale, who remarked, “It is better to die a hundred times than to live a life of humiliation.” This demonstrated how Ambedkar had given women the courage to stand out for their rights. In an address to the All-India Depressed Classes Women’s Conference he told women:

“Give education to your children. Instill ambition in them… Don’t be in a hurry to marry; marriage is a liability. You should not impose it upon children unless financially they are able to meet the liabilities arising from them. Above all let each girl who marries stand up to her husband, claim to be her husband’s friend ad equal, and refuse to be his slave.”

In his previous essays, “The women and counter revolution” and “The riddle of women,” he also made the case that, prior to Manu, women were on a level with men. Kautilya even held the opinion that women might file for divorce based only on their mutual animosity. He claimed that due to the severe limitations placed on them, women’s standing was damaged and oppressed throughout the Manu era. The discussion of gender issues was strongly started by Ambedkar, who highlighted the caste system’s exclusivity and the Hindu text Manusmriti as contributing factors to the marginalisation of Indian women. Following his thorough comparative investigation of the Buddhist scriptures, Ambedkar refuted the Eve’s Weekly assertion and proceeded to characterise the Manusmriti as one of the most regressive writings that assigns submissive positions to women in India. Manusmiriti’s sermons are still viewed as inappropriate and dangerous for the woman in issue because of Ambedkar’s persuasive argument. Thoroughly educated, Ambedkar examined old Hindu texts and said that

At one time a woman was entitled to Upanayana (seeking enlightenment or knowledge) is clear from Atharva Veda. From Srauta Sutras (Auxiliary texts of Samaveda) it is clear that women could repeat the mantras of the Vedas, and that women were taught to read Vedas. Panini Ashtaadhaya bears testimony to the fact that women attended Gurukul (college) Ambedkar drew attention to the oppressive laws found in Manusmriti that govern the behaviour of Hindu women. These laws consist of an oppressive precept that controls Hindu women in accordance with the commands of males. However, he had pointed out that there were very few of these women, and those that were involved in religious rites belonged to the highest caste or class. Ambedkar drew attention to the oppressive regulations found in Manusmriti that govern the behaviour of Hindu women. These regulations include the “Laws of Manu,” which are a set of oppressive restrictions that force Hindu women to obey men’s orders. Ambedkar persistently emphasised the importance of valuing human dignity, particularly as it relates to how an individual is perceived by others. This encouraged Indian women to overcome the barriers of caste and class-based subjugation, which were historically upheld by discriminatory Hindu codes that upheld Brahmanical patriarchy. The critique of Hindu legendary figures seen in “The Riddles of Rama and Krishna” by Dr. Ambedkar came next. His critique is centred on gender. He claims that the figures from Indian mythology are predominantly androcentric. Women are portrayed in these writings as weak, naive, and mischievous people who are unqualified for independence, while males are exalted for their actions. In addition, they explain punishment for women who do not complete their obligations and put an onus on them to continuously demonstrate their chastity, virtue, piety, and ideals. Dr Ambedkar’s one of the challenges to Hinduism is his explanation for why violence against women in Brahmanical patriarchy is inherited in nature. He views Rama as not an ideal husband. For him, he was cruel and someone who abandoned his wife to fulfil his Kshatriya (military or ruling class) dharma. In the same way, he criticised Lord Krishna as someone who is polygamous, having eight principal wives won in war or carried away from swayamvara (practice in which a girl of marriageable age chose a husband from a group of suitors) weddings and consorts inherited from the harem of a defeated king.

But as he had pointed out, there were very few of these women, and those who were part of religious rites belonged to higher castes or social classes. There has never been a more outstanding or significant work than Ambedkar’s critique of Hindu scriptures about theorizations of upper-caste and Dalit women in the Indian social structure. Dalit women’s memoirs of Ambedkar as an inspiration are gathered by Urmila Pawar and Meenakshi Moon (2008) in their book We also Made History: Women in Ambedkarite Movement. To uncover the experiences of Dalit women recounting how Ambedkar influenced them, these Dalit researchers undertook a great deal of fieldwork and significant travel throughout India. It is widely acknowledged among Dalit women that Ambedkar worked to provide Dalit women a new place in public life, one as speakers and chairpersons of public gatherings, resolution movers and seconders, and instructors. This reflected the feminism of Ambedkar and his efforts to emancipate women from the oppressive concepts embraced by Hinduism. Well before Savarna feminists usurped his appeal, Ambedkar organised a campaign for equal partnership in marriage. Thousands of men and women were motivated by Dr. Ambedkar, who served as a mobiliser against social injustice, to fight for their rights and create a society founded on the values of equality, justice, and brotherhood. In the long term, this cleared the path for Dalit Feminism to flourish. Alongside males, women were urged by Dr. Ambedkar to join the campaign. Dalit women have benefited greatly from the lectures and ideas of Dr. Ambedkar. In one of his remarks, he said:

In a real sense, the question of the abolition of Untouchability is not that of men but of you, women. You gave birth to us men. You know how other people treat us – even inferior than animals. Sometimes, they don’t even bear our shadow. Other people get respected positions in courts and offices. But we, born from your womb, cannot even get a job as a Police Constable. What will you answer if you are asked why did you give us birth? What is the difference between children born to kayastha and other “Touchable” women sitting right here, and children like us born to you? You must realise that whatever sanctity Brahmin women have, you have it too; whatever character they have, you have too. In fact the courage and daring that you possess is lacking among Brahmin women. Why should your child be deprived of even Human Rights? If this is so, why then the child born to Brahmin women is universally acceptable, while a child born to you faces insults everywhere? If you think about this, either you will have to stop producing offspring, or you will have to get rid of the stigma that has been put on them because of you. You have to do one of the two. Take an oath that you will not live under this stigma. As men are determined about emancipation, you should do the same. You should educate your daughter as well. Knowledge and education are not only for men only. It is necessary for women too. If you wish to reform your next generation, you must give education to girls as well.

Babasaheb Ambedkar was a vocal critic of the situation of women in India and constantly rebelled against the repressive aspects of Indian culture, particularly Hindu society. There is still work to be done to fulfil his dreams of gender equality. So, even today, his work and thoughts are of utmost relevance. Nearly a century ago, Ambedkar sought to change inheritance rules to better benefit Indian women. Being what Gramsci would refer to as an “organic” thinker, he saw that sermons or ideal preaching alone could not elevate women’s status in society. In Gendering Caste: Through a Feminist Lens (2006), Chakravarti argues logically that Ambedkar was ‘able to go much further in their understanding of women’s oppression’ because he possessed the epistemic privilege of coming from the marginalised sociological position, which allowed him to critique castes. He, therefore, realised that political and constitutional exigencies, as well as societal knowledge of women’s autonomy, were equally important for Indian women’s liberation and could not be achieved via simple conversion of heart.

The Question of Indian Women: Ambedkar’s Reception by Upper Caste Women

Dalit women’s concerns have seldom been taken into consideration by the rhetoric of the former mainstream upper-caste Indian feminist groups, which has likewise neglected Ambedkar and his writings. Anupama Rao, Sharmila Rege, and Uma Chakravarti are a few remarkable upper-caste women scholars who use the caste system as a weapon against oppressive patriarchal forces. In the discourse on Dalit women, scholars like Gopal Guru (1995) have drawn inspiration from Ambedkar to theorise on the position of Dalit women and identify the key distinctions between the reasons why “Dalit Women Talk Differently” and the issues that must be considered when “representing Dalit women, both at the level of theory and practice.” These ideas have been discussed repeatedly. Dalit women argue that speaking in a distinct way is justified by internal (the patriarchal dominance among the Dalits) and external (non-Dalit forces) causes that homogenise their problems. (Ibid, p. 2548-2550) Because Dalit women are paid less for fieldwork, endure unsanitary working conditions, and are subjected to sexual violence—which is a more fundamental form of caste atrocity than sexual barbarism—they are marginalised differently from upper-caste women, according to Dalit women, who have challenged mainstream upper-caste feminism in India. When Dalit women are portrayed in a caste-based manner, their predicament becomes very painful. The Dalit movement brings their gendered status to the forefront more so than their caste. In response, Dalit women put their identity as women second and their community’s members first. According to Badri Narayan (2011, p. 69).

For Dalit women, their Dalit identity overrides other identities and Dalit women see themselves, first and foremost, as Dalits. Being a woman determines the form and intensity of the violence and oppression which they face, primarily, because they are Dalits. The question of iniquitous gender relations within the Dalits communities gets relegated to second place for them, as they feel it is more important to liberate themselves from being looked upon by the upper castes as being socially and culturally inferior.

Sexual assault against Dalit women is, therefore, a gendered and caste-specific type of criminality. Many sexual offences that ended in the victims’ deaths might be found by a google search. The precarious nature of Dalit women’s status puts them at risk at this particular moment. With the exception of Ambedkar, no Dalit scholar has made significant contributions to the cause of their rights or developed theories on the hardships and circumstances faced by Dalit women as a result of discriminatory patriarchy. Until recently, Ambedkar was not seen by Indian feminists as an intellectual who theorised about the status of women in India in relation to their aspirations. Ambedkar’s well-known image as a Dalit leader or as someone who has fought for the emancipation of Dalits is often invoked while discussing him. Anyone may quickly see Ambedkar as the Dalits’ Messiah just by mentioning him and his contributions. His widespread appeal as a Dalit icon has eclipsed his general efforts to change the existing quo. Ambedkar is becoming more difficult to remove from this context. Since Ambedkar’s contributions to women’s emancipation are not widely acknowledged, his writings about the empowerment of Indian women are not as widely read as his writings on caste. Caste-related literature like Who Were the Shudras? and Annihilation of Caste (1935) are easily accessible in bookstores and have also been a part of the Dalit identity search pamphlet culture. He was a man of many dreams; he tried to end inequality and establish justice in every conceivable sphere. The systematic disregard for Ambedkar’s writings is a moral attack on ignorance and epistemic knowledge in the pursuit of developing an all-encompassing Indian academic perspective. Regretfully, Ambedkar’s legacy mostly consists of his support for the untouchables’ struggle, his critique of the caste system, and his tenuous feminist credentials. Ambedkar’s progressive approach to bringing about significant improvements in women’s status in India is praiseworthy since women’s empowerment would have remained a theoretical concept in the absence of a practical remedy to gender injustice. Taking into account Ambedkar’s contributions and political arrangements for Indian women, it is indisputable that Ambedkar is the first feminist of independent India, having fought tirelessly for the rights of Dalit and upper-caste women alike.

Conclusion

For all of the Vedic era, Indian women enjoyed the same status as men—a fact that many Indian thinkers take great pleasure in pointing out. The declining state of their circumstances is attributed to Manu’s retrogressive codifications in the Hindu religious law book Manusmriti during the post-Vedic era and his later attempts to curtail their freedom after Muslim conquests in order to maintain their dignity. These laws got so severe that Hindu wives were burnt alive on their husbands’ funeral pyres. Child marriage, the purdah (veil) system, and the forced widowhood system are only a few of the terrible traditions that the faith condones. But women have never been and currently do not form a monolithic group. Women’s position is influenced by the caste groups they belong to as well.

Babasaheb Ambedkar was in favour of taking action to better the status of women. He supported the idea that the Hindu Code Bill should be amended in the legislature. Ambedkar’s literature and philosophical ideas are crucial in the modern period. He thought that women might improve through education. In his final address, he acknowledged that women had a right to a decent existence and that they should be treated with respect in society. He cited the renowned words of Irish Patriot Daniel O’Connal: “No man can be grateful at the expense of his honour, and no lady at the expense of her virginity.” And no nation can be thankful at the expense of his freedom.” In his well-known book “Pakistan and the Partition of India,” he also expressed the view that the religious stigmas and traditions constrained women’s standing within the Muslim community. He spoke about the state of women’s life overall. Women ought to be treated equally and given the same status, he said. He persisted in the legislature, advocating significant changes and alterations to the Hindu Code bill. He also pushed and pleaded with every parliamentarian to help the measure pass the house. He ultimately resigned for the same cause. Even now, all Indians may benefit from the teachings and concepts of Dr. Ambedkar, not only women. The ladies from lower caste groups or Dalits were/are in the most pitiful circumstances. Within the mainstream of Indian feminism, they have always remained obscure. With rare exceptions, today’s mainstream feminists have similarly disregarded the problems faced by Dalit women. They also frequently downplay the role that Ambedkar played in advancing their cause as a warrior against patriarchy. He had a significant role in the unfair treatment of women and gender inequality. He spoke out against many forms of injustice against women on a regular basis. “Unity is meaningless without the accompaniment of women,” he declared with pride. Without educated women, education is useless, and without women’s power, agitation is insufficient. It is only fitting to refer to Dr B.R. Ambedkar as the Dalit people’s messiah, given his unwavering efforts and tenacious character in giving voice to the voiceless.

Endnotes:

1 Ambedkar, 2014, Vol 14, Part one, page 6

2 https://dalithistorymonth.medium.com/the-hindu-code-bill-babasaheb-ambedkar-and-his-contribution to-women’s-rights-in-india-872387c53758

References

Ambedkar, B.R. (1987) “Women and Counter Revolution” Riddles of Hindu Women” in Dr. Baba Saheb Ambedkar: Writings and Speeches, Vol. 3, Department of Education, Govt of Maharashtra

Ambedkar, B. R. (2014) “Hindu Inter Caste Marriage Regulating and Validating Bill.” Ed. Vasant Moon. Dr. Babsaheb Ambedkar: Writings and Speeches, Vol. 14. Part one. Bombay: Education Department. Government of Maharashtra. Dr. Ambedkar Foundation: New Delhi.

Ambedkar, B. R. (2014) “ Caste in India: Their Mechanism, Genesis and Development .” Ed. Vasant Moon. Dr. Babsaheb Ambedkar: Writings and Speeches, Vol. 1. Bombay: Education Department. Government of Maharashtra. Dr. Ambedkar Foundation: New Delhi.

Ambedkar, B. R. (2014) “ Progress of the Community is Measured by Progress of Women.” Ed. Vasant Moon. Dr. Babsaheb Ambedkar: Writings and Speeches, Vol. 17. Part Three. Bombay: Education Department. Government of Maharashtra. Dr. Ambedkar Foundation: New Delhi.

Ambedkar, B.R. (2014). “Castes In India: Their Mechanism, Genesis And Development.” Ed. Moon, V. Dr.Babasaheb Ambedkar: Writings and Speeches, Vol. 1. Bombay: Education Department, Government of Maharashtra, 1979, Retrieved from http://www.columbia.edu/ itc/mealac/pritchett/00ambedkar/txt_ambedkar_castes.html

Ambedkar, B. (1987). Women and Counter Revolution “Riddles of Hindu Women” in Dr. Baba Saheb Ambedkar: Writings and Speeches. Department of Education. Govt of Maharashtra.

Ambedkar, B. (1987). Women and Counter Revolution “Riddles of Hindu Women” in Dr. Baba Saheb Ambedkar: Writings and Speeches. Department of Education. Govt of Maharashtra.

Anand, A. (2013). Role of Dr. Ambedkar in Women empowerment. South-asian Journal Of Multidisciplinary Studies, 3(6), 15-29.

Arpita Giri (2021). Revisiting the writings of Dr B.R. Ambedkar through the feminist discourse http://mainstreamweekly.net/article10819.html

Banningan, John A. “The Hindu Code Bill.” Far Eastern Survey, vol. 21, no. 17, 1952, pp. 173–176. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3024109. Accessed 2Oct. 2020.

E. H. F. “Social Reform in India: The Hindu Code Bill.” The World Today, vol. 8, no. 3, 1952, pp. 123–132. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40392503. Accessed 4 Oct. 2020

Chaudhury, M. (2004). Feminism in India. New Delhi, India: Kali for Women and Women Unlimited.

Chakravarti, U. (1989). Whatever happened to the Vedic dasi? Orientalism, Nationalism, and a Script for the , in Sangari, K., & Sudesh Vaid (Eds.) Recasting Women: Essays in Colonial history. New Delhi: Kali for women. Retrieved from http://jan.ucc.nau.edu/~sj6/Sangari%20and%20Vaid%20Introduction.pdf

Elancheran, S. (2018). Dr Ambedkar’s vision of equality through the Hindu Code Bill, Ambedkar King Study Circle, USA, retrieved from https://akscusa.org/2018/04/24/drambedkar’s-vision- of-equality-through-hindu-code-bill/

Guru, Gopal. (1995). Dalit women talk differently. Economic and Political Weekly,30(41/42).Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/4403327

Ilaiah, K. (2001). Dalitism vs Brahmanism: The epistemological conflict in history. In Shah, Ghanshyam (Ed) Dalit identity and politics:cultural subordination and the dalit challenge. Vol.2. New Delhi: Sage

Kamei, S. (2011). Customary inheritance practices and women among the Kabui Naga of Manipur. Indian Anthropologist, 41(1), 55–69

Keer, Dhananjay. (1990). From dust to doye.Dr. Ambedkar: Life and Mission. Mumbai: Popular Prakashan.

Manusmriti: The Laws of Manu 1500. www.globalgreybooks.com Retrieved from https://www.islamawareness.net/Hinduism/manusmriti.pdf

Or https://www.globalgreyebooks.com/laws-of-manu-ebook.htm

Rege, S. (2013). Against the madness of Manu: B.R. Ambedkar’s writings on Brahmanical Patriarchy. New Delhi: Navayana.

Rege, S. (2016). Education as Tritiya Netra: towards Phule-Ambedkarite Feminist Pedagogical Practice. In Chakravarti, U. (Ed.) Thinking gender, doing gender: feminist scholarship and practice today. Shimla: Orient Blackswan. P 15-16

Rodrigues, V. (2002). The essential writings of BR Ambedkar. Oxford University Press. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Ray, R. (1952). The background of the Hindu code bill. Pacific Affairs, 25(3), 268–277.

Singariya, M. (2014). Dr. B R Ambedkar and women empowerment in India. Journal Of Research In Humanities and social Science, 2(1), 1-4

Som, R. (2008). Jawaharlal Nehru and the Hindu code : A victory of symbol over substance? In S. Sarkar, T. Sarkar (Eds.), Women and social reform in modern India: A reader (p. 477). Delhi, India: Indian University Press.

Sinha, C. (2007). Images of motherhood: The Hindu code bill discourse. Economic and Political Weekly, 42(43), 49–57.

+ There are no comments

Add yours