Technocratic Casteism of Indian Linkedin Professionals

– by ‘Buffalo Intellectual’

On 30 June 2020, when the California regulators filed suit in the federal court against Cisco Systems Inc for caste discrimination against one of its employees by his Indian peers, it brought into sharp focus the invisibilized mores of casteism in the tech-industry. For long, the Indian ‘techies’ have been positioned by the mainstream media as icons of true meritocracy and visual symbols of a new, ‘Shining’ India which is shedding the archaic global associations of the nation as infested with endemic poverty, superstition and backwardness. However, hidden in this convenient commentary is the fact that the superstition and barbarism of casteism is very closely rooted in this industry.

Erasure of caste commentary while practising its exclusions is a hallmark of Brahminical social structures. In true conformity with that pattern, similar discourse can be observed on LinkedIn- the job search and networking social media platform, which is rife with tech and corporate professionals.

In the early 2000s, Surinder Jodhka and Catherine Newman conducted a study (1) with 25 HR managers of large firms based in New Delhi who together employed over 190,000 fulltime and 63,000 outsourced workers, across industries ranging from e-commerce to communications to hospitality and retail among others. Their findings indicated that while all the HR managers said they did not look at the caste while hiring, they did insist that they preferred folks from ‘good background and family’ and ‘educated parents’ with ‘good culture’. Any sociologist familiar with Indian social structures will immediately tell you that these are nothing but euphemisms for upper-caste families, as these are the sites where structural privilege has accrued through generations. ‘Good culture’ and being ‘sanskaari’ is often synonymous in upper-caste circles as being deeply embedded with brahminical virtues and ‘polished social behaviour’.

A cursory stroll down LinkedIn suggests that most people are curating their profiles to project exactly these attributes. Too many people have listed their personalities as “digital storytellers” or some such, and subsequently, their personal posts are often framed as insightful anecdotes which fit the cliched, hackneyed ‘wisdom’ one can find on Google quotes. They usually contrived stories, featuring some scene at a meeting, or an email exchange or a job interview, are usually concluded by some inane life-lesson. A collection of these could verily be compiled as a millennial version of Aesop’s fables for the modern office. These ‘insightful’ lessons are usually something to do with treating your employees right, or humility at work and learning from unexpected quarters, or asking for your employer to pay you what you deserve, etc. These scenes are featured usually in top white-collar job offices and are rarely ever concerned with insights or dignity of the lowest end of the service staff. The peons, the cleaners, the office helpers only make an appearance as case-studies of fortitude and discipline, smiling even in the face of long hours and low pay.

Given the fact that there is a lop-sided caste representation with upper-castes in higher executive positions, and Bahujan labor in service roles- I read these anecdotes as a semiotic sanitizing of the workspace discourse as one which only features upper-caste issues.

The second feature of LinkedIn discourse is the technocratic fascination with peddling buzzwords. Coding is the latest fascination, crypto-currency, big data analytics, quantum computing and digital marketing are the keywords of the season. These posts almost always feature insider knowledge which is positioned as crucial to the market economy. People will seek out and attend certification workshops whose meaningless digital certificates are proudly displayed as social trophies. In and of itself, there is little conversation on LinkedIn, if such certifications are actually upgrading skills? Are they really necessary? Do the jobs require such skills, and if so, how many such jobs exist?

In truth, such digital trophies are by themselves a form of digital ‘capital’ even if the program that has certified them, is ultimately meaningless in the deflating economy of a fascist society.

These digital trophies don’t come free. There are often entry fees. On LinkedIn, it is much more acceptable to pitch paid workshops and consultancies, as it is seen as a professional-development expense. This is obviously a gatekeeping obstacle, which keeps out lower-income professionals, who are not only disadvantaged by their social strata, but now have no hope of being seen as ‘competitive’ since the definition of a ‘good candidate’ is getting linked to how many digital trophies (which you have to pay for) you can collect. Ironically, the people who participate in this digital junk economy have an internal mythology of being driven, go-getters who are constantly working to upgrade themselves, and thus talk down at inclusivity in opportunity by dismissing it as ‘free hand-outs’. They conveniently invisibilize their structural privilege in not just money to access these workshops, but also the social and cultural networks which in the first place makes them aware of which skill upgrades to pursue. This is once again typical of Brahminical spaces, where innate advantages and privileges are invisibilized and hostility is directed at ‘outsiders’ who do not have the access to the insider-talk of such spaces.

This also brings me to the third feature of LinkedIn’s exclusionary casteism, namely the hiring notices. It is becoming increasingly common practice for firms to advertise openings and internships only on the platform. This practice, while may be of help to HR simplifying things, also excludes a huge number of potential applicants. This is a worrying problem but sadly HR in Indian firms are not spending sleepless nights worrying about the lack of diversity hires in their offices (probably because HR in most firms is also almost exclusively upper-caste themselves). LinkedIn hiring notices immediately restricts the potential pool of applicants to those who have the knowledge or wherewithal to religiously follow firms and top managers of their interest areas. LinkedIn also has a paid premier tier called ‘LinkedIn Gold’ which gives added advantage to job seekers in this arena.

Where LinkedIn is different in this respect from conventional job-hunting portals such as Monster.com etc, is that the latter are not social media. LinkedIn rewards potential hires based on how well they ‘curate’ their profile and how many recommendations they can collect (and let’s be honest, most of these are not organic but solicited and given on a quid pro quo basis). A LinkedIn profile full of digital trophies, modern office Aesop’s fable type of inane anecdotes and recommendations by friends, goes beyond the CV. A lot of these variables hinge on cultural sophistry and monetary access.

It is particularly depressing to see even young Savarna profiles on LinkedIn, posting antiseptic, bland and market-friendly posts while a cursory browse through their Twitter or Instagram will reveal a vibrant curation of feminist, queer and anti-fascism posts. Consciously or not, even the young Savarnas know that if you bring that kind of ‘content’ on your LinkedIn profile, it will hurt your employment opportunities. Yet, there is a respectable acceptance of posts concerning themselves with Brahminical festivals like Diwali, etc. A critical discourse analysis of this makes it very clear what the underlying definition of acceptable politics is on LinkedIn. It is not ‘apolitical’. It is so thoroughly Brahminized that Brahminism itself appears invisible. As the late David Foster Wallace would say, it is like a fish surrounded by water does not ‘see’ the water.

For Bahujan professionals, Indian LinkedIn can be a very isolating space. One never sees the word ‘caste’ anywhere yet it makes its presence felt everywhere. Deeply casteist, self-congratulatory, exclusionary, and festering with deep mediocrity- Indian LinkedIn is one of the most toxic spaces for not just an Ambedkarite, but for any politically conscious person.

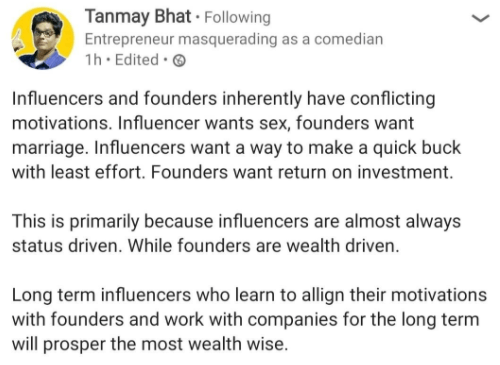

After all, it is literally the only platform where it is acceptable for an upper-caste man to post vaguely sexist jokes masquerading as ‘insights’ in public, and be applauded for it.

Example: a Digital Content Creator & Entrepreneur peddling profound ‘insight’

***

References:

1. Surinder S. Jodhkar & Katherine S. Newman, “In the name of Globalization: Meritocracy, Productivity, and Hidden language of Caste,” in Blocked by Caste: Economic Discrimination in Modern India, ed. Sukhdeo Thorat & Katherine S. Newman (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2010)

The author could be reached on Twitter at @BuffaloSpeaks

Published on 10/09/2020

+ There are no comments

Add yours