How Twitter Got Blindsided By India’s Still-toxic Caste System

Authors – Hari Bapuji and Snehanjali Chrispal

Twitter chief Jack Dorsey’s first visit to India had been going so well. He got to meet Prime Minister Narendra Modi (an avid Tweeter with 44.5 million followers), “King of Bollywood” Shah Rukh Khan (36.8 million followers), and the Dalai Lama (18.8 million followers).

Then a single tweet had him being accused of hate mongering. There was talk of an Indian boycott of Twitter, and even of developing a rival Indian platform like China’s Weibo. A senior parliamentary official saw a case to prosecute Dorsey for attempting “to destabilise the nation”. A court in the northern state of Rajasthan ordered a police investigation.

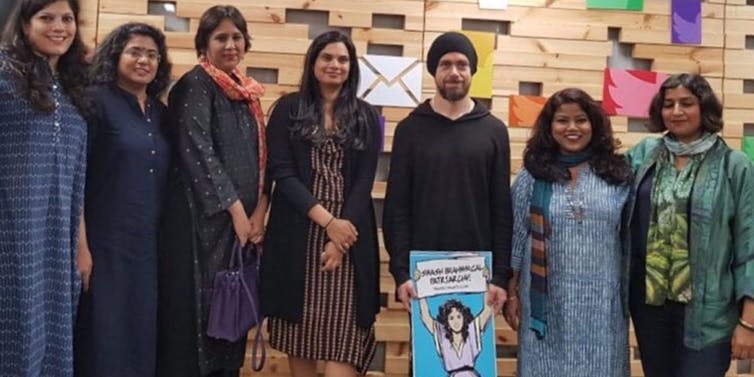

Dorsey’s offence: holding a poster that proclaimed “Smash Brahminical Patriarchy”.

Twitter’s Jack Dorsey with the ‘Smash Brahminical Patriarchy’ poster that has him accused of hate-mongering.

The poster was given to Dorsey by Sanghapali Aruna, an activist for the rights of Dalits, the bottom most group in the Indian caste system. The controversy resulting demonstrates just how potent caste remains, and how blind to it are the multinational corporations eyeing off the Indian market.

A short guide to caste …

To understand what the fuss is about, we need to understand the age-old caste system in the Indian subcontinent, and its complexities.

Caste is similar to a social class, but mobility is impossible and discrimination can occur among those of the same economic class. It is similar to the idea of race, but can be perpetuated by those within the same ethnic group. It originated in Hinduism, but has been absorbed by Muslims, Christians and Sikhs.

The system can be traced to the Manusmriti code of Hindu laws, which suggests Brahma, the Hindu god of creation, created four categories of people from his own body: Brahmins from his head, Kshatriyas from his arms, Vysyas from his thighs, and Shudras from his feet.

This origin ordained an occupational hierarchy. You inherited your caste from your father, and that determined your future. The Brahmins were the priests and advisers – and primary enforcers of the caste system. The Kshatriyas were warriors and soldiers. Then Vysyas farmers and traders. The Shudras workers and tradespeople.

Beneath the Shudras were the Dalits – the “untouchables” – tasked with all menial jobs, including cleaning and disposing of the dead.

The system imposed codes of conduct and rules for interaction between castes. Mixed marriages, for example, were forbidden. So too was physical contact with all Dalits, who were condemned to live away from the village and had no right to public places, such as temples.

Although discrimination against Dalits was outlawed by India’s constitution in 1950, caste-based prejudices live on, and are even inflamed by Dalits asserting the right to equality.

The constitution also enshrined affirmative-action programs for Dalits and other marginalised groups in the public sector, but across the Indian economy they continue to occupy the lowest rungs. Centuries of caste-based discrimination has enabled deep economic inequalities that still influence the opportunities and rewards given to individuals.

… and to patriarchy

Dalit women have the worst of it. They face discrimination from other castes, as well as from men within their own caste. They are more likely to be trafficked and subjected to contemporary slavery. They are still forced into temple prostitution known as Devdasi or Jogini systems.

Traditional ideas about gender roles still affect what is considered appropriate for women to do, what they can wear and who they can interact with. Women resisting such patriarchal notions can face reprisal, from abuse to violence, rape, and even murder.

The interrelationship between caste hierarchy and gender hierarchy in traditional Indian culture is known as the “Brahmanical social order”. That Aruna’s poster referred to “Brahminical patriarchy” has offended some as a more direct attack on Brahmins, not just the caste system. This may be reading too much into it. Others have reacted to the poster as an attack Hinduism. Yet others have been offended by a foreigner seemingly lecturing Indians on something he knows little about.

Twitter’s ecosystem challenge

It is into this landscape that Twitter’s chief lumbered.

India is Twitter’s most important developing market. Its population will soon overtake that of China, where the government blocks Twitter. Though the eight million Indians who actively use Twitter is still less than a quarter of the Americans who do, US user numbers have plateaued while the Indian market is growing at five times the global average.

Twitter is also arguably important to India. It has given Dalit women and other marginalised people a platform to voice their concerns. But it has also facilitated trolling and abuse. In mid-November Shehla Rashid, a student leader with more than 500,000 followers, quit the platform as an “SOS call to Twitter”. Describing the platform as an ecosystem of “toxicity and negativity”, she said: “It is not freedom of expression but an attack on freedom of expression.”

Listening, not hearing

This is the reason Dorsey met with Aruna and other women at the end of his India trip: to hear firsthand their concerns about the way Twitter facilitates abuse and threats.

The company’s reaction to the aftermath would not have persuaded the women they had been heard. Twitter quickly declared Dorsey was merely holding the poster because he had been given it as a gift, and that the poster’s sentiments were not Twitter’s official position. Twitter’s chief legal advisor, Indian-born Vijaya Gadde, apologised for failing to be “an impartial platform for all”.

Such a response was “hypocritical”, declared journalist Sidharth Bhatia, because Twitter “apologised to those very people whom the poster was calling out, only because they are noisier and better organised”.

Multinational blind spots

How could Twitter be blindsided by caste?

One reason may be a problem shared by most multinational companies operating in India. They might promote gender and ethnic diversity in their home countries, but caste is less obvious to them. Unconsciously they might even be perpetuating the caste system.

When multinationals hire, they prefer people with a certain type of family background and cosmopolitan profile. Those from upper castes – beneficiaries of accumulated advantage over centuries – tend to fit that bill. As a result they are more likely to get hired and promoted to positions of power. Thus, the caste system is unconsciously replicated.

Multinationals – and indeed all companies in India interested in its future prosperity – need to think about the ways in which caste inequalities operate. They must work to improve caste diversity in their ranks, such as through including caste in audits and educating their workforce.

Twitter has an additional challenge. It needs to ensure its platform is not a tool of caste and other forms of discrimination. Taking responsibility and cleaning up trolling, bullying and harassment on its platform would be a major public service to Indian society – and to democratic conversations everywhere.

—

Dr. Hari Bapuji is a Professor in the Department of Management and Marketing, Faculty of Business and Economics, The University of Melbourne, Australia.

Snehanjali Chrispal is a PhD candidate at University of Melbourne

The article was originally published in The Conversation.

+ There are no comments

Add yours