Caste and Graded Inequality

Stated in the language of equality and inequality, this means that the Brahmin is the highest because he can be the slave of nobody but is entitled to keep a person of any class as his slave. The Shudra is the lowest because everybody can keep him as his slave but he can keep no one as his slave except a Shudra. The place assigned to the Kshatriya and the Vaishya introduces the system of graded inequality.

A Kshatriya, while he is inferior to the Brahmin, he can be the slave of the Brahmin. While he is yet superior to the Vaishyas and the Shudras because he can keep them as his slaves, the Vaishyas and the Shudras have no right to keep a Kshatriya as his slave. Similarly, a Vaishya, while he is inferior to the Brahmins and the Kshatriyas, because they can keep him as their slave and he cannot keep any one of them as his slave, is proud that he is at least superior to the Shudra because he can keep the Shudra as his slave while the Shudra cannot keep the Vaishya as his slave.

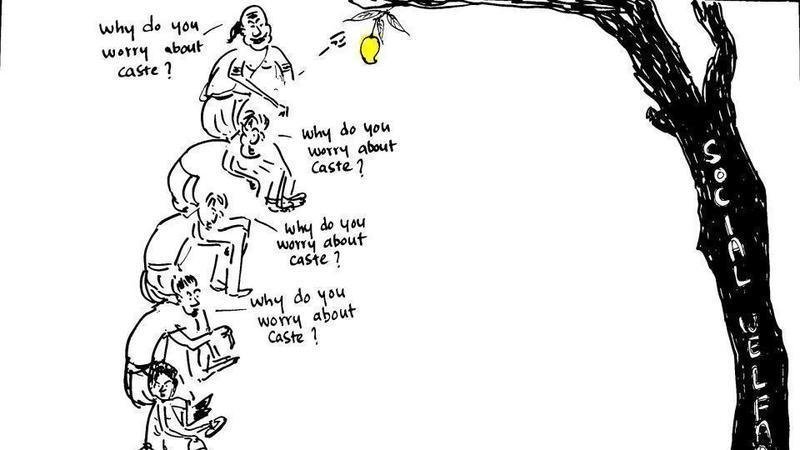

Such is the principle of graded inequality which Brahmanism injected into the bone and the marrow of the people. Nothing worse to paralyse society to overthrow inequity could have been done. Although its effects have not been clearly noticed there can be no doubt that because of it the Hindus have been stricken with palsy. Students of social organization have been content with noting the difference between equality and inequality. None have realized that in addition to equality and inequality, there is such a thing as graded inequality.

Yet, inequality is not half so dangerous as graded inequality. Inequality carries within itself the seeds of its own destruction. Inequality does not last long. Under pure and simple inequality, two things happen. It creates general discontent which forms the seed of revolution. Secondly, it makes the sufferers combine against a common foe and on a common grievance. But the nature and circumstances of the system of graded inequality leave no room for either of these two things to happen.

The system of graded inequality prevents the rise of general discontent against inequity. It cannot, therefore, become the storm centre of a revolution.

Secondly, the sufferers under inequality becoming unequal both in terms of the benefit and the burden, there is no possibility of a general combination of all classes to overthrow the inequity. To make the thing concrete, the Brahmanic law of marriage is full of inequity.

The right of a Brahmin to take a woman from the classes below him but not to give a woman to them is in inequity. But the Kshatriya, Vaishya and Shudra will not combine to destroy it. The Kshatriya resents this right of the Brahmin. But he will not combine with the Vaishya or the Shudra and that is for two reasons. Firstly, because he is satisfied that if the Brahmin has the right to take the women of three communities, the Kshatriya has the right to appropriate the women of two communities. He does not suffer so much as the other two. Secondly, if he joins in a general revolution against this marriage-inequity, in one way he will rise to the level of the Brahmins, but in another way all will be equal, which to him means that the Vaishyas and the Shudras will rise to his level i.e. they will claim Kshatriya women—which means he will fall to their level. Take any other inequity and think of a revolt against it. The same social psychology will show that a general rebellion against it is impossible.

One of the reasons why there has been no revolution against Brahmanism and its inequities is due entirely to the principle of graded inequality. It is a system of permitting a share in the spoils with a view to enlist them to support the spoils system. It is a system full of low cunning, which man could have invented to perpetuate inequity and to profit by it. For it is nothing else but inviting people to share in inequity in order that they may all be supporters of inequity.

Source – BAWS, Vol. 3, pp. 319–20

+ There are no comments

Add yours