3rd January in Dalit History – Remembering Jaipal Singh Munda: Unsung Hockey Champion Who Won An Olympic Gold For India

It wasn’t Subhash Chandra Bose alone who turned down the Indian Civil Service. Jaipal Singh Munda did, too, and went on to become the voice of the Adivasis in the Constituent Assembly, where he spoke up against casteism and patriarchy in mainstream Indian society. A. K. Biswas looks back at his life.

There are few icons of the tribal heartland who are given the importance they deserve in Indian history. They are not only segregated, but also excluded. The Tribals themselves were exploited and cheated unmercifully by the outsiders. This went on unhindered, on a savage scale, for centuries. No wonder, Tribals are suspicious of the non-Tribals – their immoral motives and dark intentions.

The Santhals rose in revolt in 1855. A section of society tries to project their revolt as an uprising against the British rule. But the Santhals revolt was actually directed against outsiders in general, who, in their language, were called dikus – cheats, exploiters and extortionists.

Birsa Munda-led rebellion or “Ulgulan”, meaning “Great Tumult” (1899-1900), which took place in the south of Ranchi, was a landmark in the agrarian history of tribal India. It was against encroachment and dispossession of tribal land. It was a manifestation of the consequent frustration and anger among the deprived tribal communities. The Mundas traditionally enjoyed a preferential rent rate as the “khuntkattidar” or the original clearer of the forest. But during the 19th century, they had seen the “khuntkatti” land system being eroded by the “jagirdars” and “thikadars” – the outsiders who arrived as merchants and moneylenders and gradually invaded their paradise in the forests.

Birsa Munda was born in the Khunti subdivision of Ranchi district on 15 November 1875. He lived little less than 25 years, breathing his last on 9 June 1900 in prison. His short life left a deep imprint on the tribal communities.

Jaipal Singh Munda was born three years after Birsa Munda’s death. Jaipal too belonged to the Khunti subdivision of Ranchi district (Khunti is now a district carved out of Ranchi in Jharkhand). Jaipal was born on 3 January 1903 in Tapkara, a Munda village. Birsa’s struggle had carved out a permanent space in history for Jaipal.

Jaipal’s family had embraced Christianity. Missionaries of the SPG Mission, Church of England, had noticed early sparks of his talent and leadership qualities. After initial schooling in his village, Jaipal was admitted to St Paul’s School, Ranchi, run by the missionaries. His amiable character and qualities enamoured all those who came in touch with him. Early in his youth, his exceptional calibre as a hockey player shone.

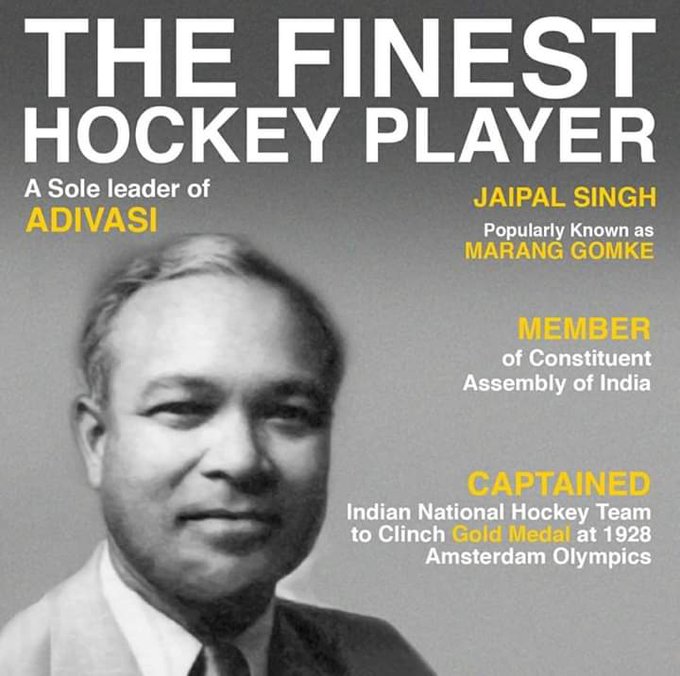

Jaipal Singh Munda

The principal of St Paul’s became his patron and sent him to Oxford University, England, for higher education. Jaipal did not take much time to demonstrate his mettle as an ace hockey player in the celebrated university and was soon part of the Oxford University hockey team. The hallmarks of his game as a deep defender were his clean tackling, sensible game-play and well-directed hard hits. He was the most versatile player in the Oxford University hockey team. His contribution to the university hockey team earned him recognition and he became the first Indian student to be conferred the Oxford Blue in Hockey.

At Oxford, Jaipal’s literary talents exploded as a prolific sports – particularly hockey – columnist. He regularly contributed to leading British journals and his articles were widely acclaimed by readers. In 1928, the Netherlands hosted the Summer Olympics in Amsterdam. Jaipal was chosen to captain the Indian hockey team for this event. But he had a choice to make: either turn down the offer to play for India or face expulsion from the prestigious Indian Civil Service.

PATRIOTISM BEFORE PERSONAL INTEREST

Jaipal passed his Economics (Honours) examinations with flying colours. He then took the Indian Civil Service (ICS) examinations conducted by the British in India for bureaucracy aspirants. Those Indians who had qualified before him hailed from rich, land-owning aristocratic families. Jaipal was a striking exception. He entered the ICS with the highest marks in the interview.

It was while he was undergoing training in England as a probationer that he got the call-up to represent India in the Amsterdam Summer Olympics. He was asked to travel to Amsterdam and join the team immediately. Jaipal approached the authorities at the India Office, London, seeking leave of absence so that he could proceed to Amsterdam. The India Office rejected his application outright.

Indian hockey team in the 1928 Olympics after their first match versus Austria. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

He was in a dilemma – whether to play for the country or hold on to the straitjacketed ICS – and he picked the former. Subhash Chandra Bose has said that nobody from India had, before him, voluntarily foregone an opportunity for a career in the ICS which held in store great opportunities, social recognition, unprecedented dignity, a secure life and unquestioned authority with the British at the helm of power. Sadly, Subhash Chandra Bose had erred in overlooking this sacrifice of Jaipal Singh Munda.

Jaipal responded to the dictates of his heart and defied the established conformism. He left for Amsterdam fully aware of the consequence – for he stood virtually dismissed. Such indiscipline on the part of any probationer is not tolerated, much less so by the India Office at the time, which remote-controlled the Government of India from London. Indeed, such brazen defiance by a probationer was considered unbecoming of a budding ICS.

The Indian hockey team for Amsterdam Olympics was announced: Jaipal Singh (Captain), Richard Allen, Dhyan Chand, Maurice Gateley, William Good-Cullen, Leslie Hammond, Feroze Khan, George Marthins, Rex Norris, Broome Pinniger (vice-captain), Michael Rocque, Frederic Seaman, Ali Shaukat and Sayed Yusuf. The league stage of the tournament involved two groups, A and B. In all, 31 players scored 69 goals in 18 matches. Of them, India (from group A) scored 29 goals – Dhyan Chand scored 14; Feroze Khan and George Martins scored five each; Frederic Seaman, three; and Ali Saukat and Maurice Gateley, one each. India defeated Holland 3-0 in the final. Germany and Belgium had to be content with the third and fourth positions, respectively.

Jaipal did not play the final against Holland. Serious differences had cropped up between team manager A.B. Rossier and the captain. Jaipal had gracefully opted out of the final match. Vice-Captain Broome Pinniger stewarded the team to a convincing victory over Holland. This was India’s first ever Olympics gold.

MARRIAGE

Jaipal returned to England after the 1928 Olympics. Then Viceroy of India, Lord Irwin, personally congratulated him for his excellent captaincy and the team’s performance and victory. The India Office appeared to have softened their stance on the ICS. Perhaps prodded by Irwin, Jaipal was asked to rejoin the ICS probation, which, however, was extended by a year. He felt humiliated by the decision to extend his probation. He found it discriminatory and unacceptable and consciously defied the orders of the India Office a second time. He returned to India and joined a multinational oil major, Burmah Shell, which had offered him the position of a senior executive while he was still in England.

In metropolitan Calcutta, where he was based, Jaipal met his future wife, Tara Winfred Majumdar. She was the granddaughter of Womesh Chunder Bonnerjee, one of the founders of the Indian National Congress and its first president (1885). Their marriage, however, did not last long.

Teaching assignments took Jaipal to different places – from Raipur (the present capital of Chhattisgarh) in the Central Provinces and Berar, to the Gold Coast in Ghana, Africa, and finally, to Rajputana. In Raipur, he became the principal of Rajkumar College. Here, he became the target of caste hatred and discrimination, despite his outstanding educational qualifications; accomplishments, including those in sports; competence; and leadership qualities.

Rajkumar College was the exclusive preserve and grooming ground of young men from Indian princely and feudal families in the company of European students. The parents found it unpalatable and galling to have their children educated under a Tribal. The Europeans too were uncomfortable. So, Jaipal proceeded to the Gold Coast, Africa, again on a teaching assignment. Gradually, his career changed tracks.

When he returned to India, he was appointed Colonization Minister and Revenue Commissioner in the princely state of Bikaner. This stint, in which he was unimpeachable, earned him further laurels. He was elevated to the post of Foreign Secretary of the state of Bikaner.

Jaipal Singh Munda sketch (Source: Adivasi Resurgence)

BACK AMONG HIS PEOPLE

At this stage, he felt a profound urge to do something for his people, the neglected and exploited tribal communities in Chota Nagpur in Bihar. He returned to Bihar and met Dr Rajendra Prasad, president of the Bihar Provincial Congress Committee, at Sadaquat Ashram in Patna. There, he felt, he was accorded a cold reception. If one door closes before a determined person, with his belief in himself and strength, another opens up simultaneously. The proverbial door opened for Jaipal, too.

The Governor of Bihar and Orissa, Sir Maurice Hallet, who requested him to become a member of the Bihar & Orissa Legislative Council, opened the door. He, however, politely declined the gracious offer. Then, both the Governor and Robert Russell, the chief secretary, advised him to take up the cause of the tribal people who were already in a restive mood. Jaipal Singh went to Ranchi, where Tribals gave him a warm and tumultuous welcome.

REPRESENTING HIS PEOPLE IN THE CONSTITUENT ASSEMBLY

In 1946, Jaipal was elected to the Constituent Assembly from a general constituency in Bihar. The 296-member Constituent Assembly was tasked with drafting the Constitution. Jaipal spoke for the first time in the Assembly on 19 December 1946. Introducing himself as a “jungli” – a forest dweller – he spoke of the “unknown hordes – of unrecognized warriors of freedom, the original people of India who have variously been known as backward tribes, primitive tribes, criminal tribes and everything else. Sir, I am proud to be a jungli – that is the name by which we are known in my part of the country.”

Speaking for the people living in the Chota Nagpur plateau, he supported the resolution that articulated the aspiration and sentiments of “more than 30 millions of the Adibasis” (amid cheers), because it was also “a resolution which gives expression to sentiments that throb in every heart in this country”… He added, “As a jungli, as an Adibasi, my common sense tells me, the common sense of my people tells me, that every one of us should march in that road of freedom and fight together.”

At the time, the newly independent country was brimming with emotion and idealism. However, about seven decades on, we have a deep sense of disillusionment. A tragedy has befallen the country and the masses have become the collective victims of a section of greedy, manipulative and unprincipled leaders who are intrinsically entrenched and involved in unbridled loot, unchecked corruption and blatant exploitation for

Jaipal Singh Munda captained this Indian hockey team that won the Gold in the 1928 Olympics held in Amsterdam, Holland

self-aggrandizement.

TRIBALS AND INVADING OUTSIDERS

Jaipal Singh did not mince words to ventilate the grievances of his “primitive people” who, according to him, were “shabbily treated … They have been disgracefully treated, neglected for the last 6,000 years.”

When and how did it began? Who were the men guilty of disgracing and neglecting the tribal people?

Jaipal Singh Munda told the assembly: “The history of the Indus Valley Civilization, a child of which I am, shows quite clearly that it is the newcomers – most of you here are intruders as far as I am concerned – it is the newcomers who have driven away my people from the Indus Valley to the jungle.”

This was the severest indictment possible of the “honourable men” comprising the newly elected Constituent Assembly. They were extremely accomplished men and women, elected from all parts of the country. If the historians have not placed this statement in Indian historiography, it only indicates their failure. It underlines that they had no courage to do so, and deep bias and prejudice dominated their writing and re-writing of history.

Jaipal was telling his peers about the invasion that led to the damage and destruction of the Indus Valley, which boasted of a glorious civilization. He said that the people living in the Indus Valley were driven to remote, inhospitable forests and mountains. Indeed, to declare it among the honourable members of the Constituent Assembly that they were guilty of this relentless brutality was tantamount to their public condemnation. The miserable fate of his people led him to bemoan that, “the whole history of my people is one of continuous exploitation and dispossession by the non-aboriginals of India punctuated by rebellions and disorder”.

It may be stated that 292 members of the Constituent Assembly were elected through the provincial legislative assemblies; besides, there were 93 members who represented the Indian princely states, and four members who represented the Chief Commissioners’ Provinces. They sat in silence and listened to Jaipal as he waxed eloquent on an alternate history of India. Some of them included mass leaders like Jawaharlal Nehru, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, Dr Rajendra Prasad, Dr Sarvapalli Radhakrishnan, C. Rajagopalachari, Sarojini Naidu, J.B. Kripalani and Dr Sachchidanand Sinha. The maharajas of Patiala, Bikaner and Gwalior and the Nawab of Bhopal, too, heard his speech with rapt attention.

The apathy and negligence of the Cabinet Mission with respect to the tribal people of India came up for sharp criticism in his speech. “Have we not been casually treated by the Cabinet Mission [and have not] more than 30 million people [been] completely ignored?” Representing these 30 million, he bemoaned, there are only “six tribal members in this Constituent Assembly”.

Jaipal noted that the tribal communities are a living example of an egalitarian society. He said, “There is no question of caste in my society. We are all equal.” Their unabated exploitation, he said, exhibited the dominant paradigm of the social-economic and political culture. He strongly demanded the inclusion of “more Adibasis” in the national legislature to represent their interests. A firm believer in gender equality among the tribal communities, he said, “I mean, sir, not only (Adibasi) men but women also. There are too many men in the Constituent Assembly. We want more women …” Jaipal Singh was definitely one of the first to press for the participation of women in shaping and building independent India.

In a stirring speech, Jaipal Singh told the Constituent Assembly, “You cannot teach democracy to the tribal people; you have to learn democratic ways from them. They are the most democratic people on earth.” This country should be proud of the tradition of democracy prevalent and practised by the tribal communities – free from inequality, discrimination and disadvantages imposed on one section by another without any reason and logic. “What my people require, sir, is not adequate safeguards … they require protection from the ministers. That is the position today. We do not ask for any special protection. We want to be treated like every other Indian,” he said.

On the issue of freedom and rights under Article 13 (1) (b), namely, to “assemble peaceably and without arms”, he pointed out “that this matter of the Arms Act has been very mischievously applied against the Adibasis. Certain political parties have gone to extremes to point out that because Adibasis carry bows and arrows, lathis or axes, which they do daily as a normal part of their life, which they have done for generations and generations, and what they are doing today they have done before, that they are preparing for trouble.”

He cited the example of the Oraon tribe. “We have in this Assembly only one Oraon member. Now, the Oraon group of Adibasis constitutes the fourth largest block of Adibasis in India.” Jaipal Singh highlighted the cultural traditions of the Oraons. “They have, what we call, ‘jatras’ or ‘melas’. These are annual occasions for their cultural activities. They have a certain ceremony in which the head of the Oraon village will carry the flag and the rest of them will carry lathis with them and proceed into the various ‘akhadas’ or villages. It is a festival for the people; they have done it in a harmless way for generations and generations, and, now we have been told last year and the year before last, that we should not carry weapons. I do not mind pointing out there are several members here from Bihar who will never be able to get back to their homes unless they are escorted with people and with arms. In my own part, we live in the jungles and everyone, even women, may I point out, carry what might be designated arms, but they are not arms in that sense. Whenever we have to hold meetings, if people come with their own usual things, I want to know whether it is going to be interpreted that we are assembling non-peacefully and carrying arms for an unlawful purpose. These are the only points, sir, that I want to be clarified.

“I will give one more instance. Every seven years, it is the custom in Chota Nagpur to have what they call ‘Era Sendra’ – ‘Janishikar’. Every seven years, the women dress as men and hunt in the jungles – dressed as men, mind you. That is the occasion, when, naturally, women like to show masculine prowess. They arm themselves like men with bows and arrows, lathis, bhelas and so forth. Now, sir, according to this particular Article in the Constitution, the government might interpret that women, every seven years, have been getting together for a dangerous purpose. I urge the House to do nothing that is going to upset the simple folk. They have been among the most peaceful citizens in our country and we should be very very cautious in doing anything which might be misunderstood by them and lead to trouble.”

Jaipal Singh added: “I have been traversing a lot among the Adibasis in the Adibasi tracts, and, in the last 9 years, I have traversed 1,14,000 miles, and it has given me an idea of what the Adibasis need and what this House is expected to do for them. He urged that the interests and cultural traits of Tribals needed protection and care.”

Jaipal thus was a man of many parts – an accomplished writer, a hockey wizard, an excellent orator, a visionary, an uncommon patriot and an indefatigable champion of the Adivasi cause. Jaipal stands out among current and past sports personalities with his integrity, patriotism and courage – qualities that would propel him towards becoming Marang Gomke, the great leader of the tribal people.

Source – ForwardPress

+ There are no comments

Add yours