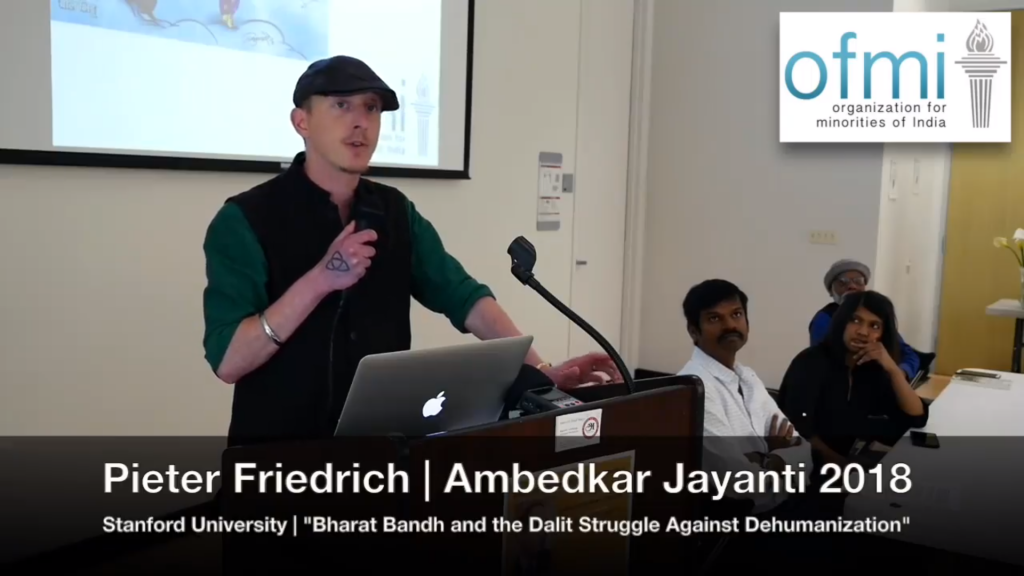

Bharat Bandh and the Dalit Struggle Against Dehumanization

Author – Pieter Friedrich

How Dalits are still, today, waging a centuries-old struggle against a system which denies them the basic dignity of identification as human beings on an equal level with all other people. How Dalits are facing down a systematic attempt at dehumanization. How Dalits are standing up today to demand recognition of their human dignity.

https://www.facebook.com/minoritiesofindia/videos/2250253541677739/

—

On April 9, 1945, Dietrich Bonhoeffer was executed by the Nazi Regime in Germany.

Bonhoeffer was a Christian pastor who spent years organizing a secret resistance against the Nazis, and was eventually arrested after the resistance movement in which he was involved attempted to assassinate Adolf Hitler.

Bonhoeffer was imprisoned for a year and a half. He used that time productively. His writings were later published as a book called “Letters and Papers From Prison.”

Putting pen to paper in his prison cell, Bonhoeffer writes, “We have for once learnt to see the great events of world history from below, from the perspective of the outcast, the suspects, the maltreated, the powerless, the oppressed, the reviled — in short, from the perspective of those who suffer.”

As we look around us at the unfolding current events which will become the “great events of world history,” can we hear the perspective of the suffering?

A month ago, in Sacramento, California, an unarmed black man was gunned down while standing in his grandmother’s backyard. The dead man was Stephon Clark. Police thought he might be vandalizing cars. A neighbor called 911 after he saw a man breaking the windows of his truck. Police showed up. They didn’t know if Stephon was the vandal or not. But they shot him, several times, in the back.

Police said Stephon had a gun. He did not have a gun. The officers who shot him knew they had done wrong. “Hey, mute,” said officers on scene, so they turned off the audio feed on their body cameras. Now the neighbor who called the police says, “It makes me never want to call 911 again. They shot an innocent person.”

Stephon’s killing has provoked ongoing protests in Sacramento. People are saying he was shot because he was black. People are saying the police harass, brutalize, and kill black people.

On April 3rd, I attended a Sacramento City Council meeting where people were speaking out in protest. A black man took the podium. With fury in his voice, he shouted, “In no way, shape, or form should I ever be deprived of my right as a person of color. I am not three percent human being. I am 100% human!”

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. explains, “No other ethnic group has been a slave on American soil.” Even today, many people of African descent still believe they must fight the same struggle fought by their ancestors — a struggle against slavery and segregation and dehumanization. Even today, many feel they are denied full citizenship rights, treated as subhuman, and subjugated. Even today, right here in California, people of African descent feel it is necessary for them to step forward and say something so simple as “I am human.”

A black man in New York, quoted in The Guardian newspaper, describes his perspective. William Jones says, “It’s like we are seen as animals. Treated like animals. It’s not easy.”

Dehumanization of blacks was the basis of slavery. According to sociologist Dr. Abby Ferber, “Historically, African Americans were defined as animals, as property to be owned by White men.” If we listen to the perspective of the outcast, the powerless, and the oppressed, we hear echoes of this narrative all around the world from people struggling to secure their human dignity.

From 1948 to 1991, South Africa suffered under apartheid, one of the most extreme forms of institutionalized segregation the world has ever witnessed.

Nomakhwezi Gcina, the daughter of anti-apartheid activist Ivy Gcina, describes her family’s suffering. “We’d be sleeping at night and the police would come kicking the doors down, wanting to know where my brother was and beating us up. They would burn our house down, arrest my mother and we would be left without a mother…. We were treated like animals.”

Another activist, M. Maluleke, states, “What hurts me most is I know that as black people we are animals to policemen. Policemen, irrespective of color, black or white, treat us as objects — like we are not human beings.”

Today, some South African activists still feel that society has not undergone the necessary transformation, that recognition of the universality of human dignity has not been fully achieved, and that black people today still face dehumanization. For example, South African politician Mbuyiseni Ndlozi spoke out in 2016, saying, “This country has a very painful past, which still seems to be our present, in which black people continue to be treated like animals.”

The treatment of African people as animals has its roots in the invasion, occupation, and subjugation of Africa by white colonial governments. Today, however, some African intellectuals suggest that the dehumanization of black people was aided and abetted by allies of the white colonists. They point, for instance, to Gandhi, the Indian politician who begin his public career as an attorney in South Africa.

Speaking from the University of Ghana, Dr. Obadele Kambon explains, “[Gandhi is] known especially amongst the black people of South Africa… as the father of apartheid.” Describing how Gandhi treated black Africans during his 21-year stint in South Africa, Dr. Kambon says, “He referred to them as ‘savage,’ ‘half-heathen,’ “one degree from an animal,’ ‘kaffir,’ which is a very derogatory term.”

To briefly dwell on Gandhi, we see from his writings how he dehumanized black Africans. He protests, “A general belief seems to prevail in the Colony that the Indians are a little better, if at all, than savages or the Natives of Africa.” Contrary to that belief, writes Gandhi, “Indians… are undoubtedly infinitely superior to the Kaffirs.” He endorses the racial policy of colonialism, declaring, “We believe also that the white race in South Africa should be the predominating race.” And, writing from prison, he says, “Kaffirs are as a rule uncivilized.… They are troublesome, very dirty and live almost like animals.”

In 1914, Gandhi returned to India from South Africa. Just as he upheld an apartheid-style system in Africa, he upheld the caste system in India, including perpetuating the subjugation of Dalit people as outcastes — or so-called “Untouchables.” According to Dalit author Sujatha Gidla, “Gandhi has never been a person for eradication of caste system.” Gidla says, “It’s a general idea that Gandhi was a champion of Untouchables. That is a really false idea. He was not only anti-Untouchable…. He was also an anti-black racist.” She adds, “During his stint in South Africa, he looked down on black people in Africa.”

The champion of the Untouchables — the Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. of India — was Dr. Bhim Rao Ambedkar, who says, “I met Mr. Gandhi in the capacity of an opponent.” In the words of Ambedkar, writing in a letter to African-American civil rights activist W.E.B. Dubois, “There is so much similarity between the position of the Untouchables in India and of the position of the Negroes in America that the study of the latter is not only natural but necessary.”

That was Ambedkar’s position in the 1940s. Today, Sujatha Gidla echoes Ambedkar. She says, “Any Untouchable who has some knowledge of the outside world, some consciousness of their oppression, they do identify with black people in America…. I identify with black people. I see the same oppression against black people here.”

W.E.B Dubois pointed out, “It is difficult to let others see the full psychological meaning of caste segregation.” Yet, in order to fully comprehend the end result of systems of oppression like racial segregation in the United States, apartheid in South Africa, or caste in India, we must understand how the oppressed experience their treatment. We must understand, from the perspective of those treated as outcaste, how they experience dehumanization.

Narendra Jadhav, a Dalit politician, describes the experiences of his family in a book entitled, Outcaste – A Memoir: Life and Triumphs of an Untouchable Family in India. Narendra’s father’s name was Damu. Describing one incident in Damu’s life in the early 1900s, he sets the scene.

Walking through a village with his father on a hot, sunny day, Damu grows thirsty. He sees a vat of water sitting underneath a tree. An upper-caste man is sitting next to it.

Narendra writes, “[Damu] went near the water and picked up an iron tumbler lying near it. A dog was resting under the shade of the tree. The man kicked the dog aside and dipped the tumbler in the water. I looked at him expectantly, but he drank it himself.” Damu is not allowed to touch the water himself. Instead, the man reluctantly dips the tumbler into the vat and pours water directly into Damu’s hands.

As Damu walks away with his father, he looks backs. In Damu’s words, “When I looked back, the dog was lapping up the water from the same vat! That was the first time I wondered if it was better to be born a dog than a Mahar.”

The Mahars — considered an Untouchable community — have been organizing resistance movements against caste since the 1800s. Jyotirao Phule was one of the earliest champions of their movement for human dignity. Amedkar continued and expanded that movement.

Since time immemorial, those treated as Untouchables have been forbidden from doing many things which other people who are fully accepted into society are allowed to do. One of the greatest taboos, however, has always been for Untouchables to enter Hindu temples.

One of Dr. Ambedkar’s earliest agitations against caste involved a movement to demand the right of temple entry for all people. In 1930, he launched the Kalaram Temple entry movement. During the Satyagraha — that is, civil rights movement — Ambedkar framed the issue in terms of a demand for recognition of the humanity of Dalits, stating,

“Whether the Hindu mind is willing to accept us as human beings, this is the question to be tested through this Satyagraha. The high caste Hindus looked down upon us and treated us even worse than cats and dogs. We wish to know whether those very Hindus would give us the status of man or not.”

In 1931, in conversation with Gandhi, Ambedkar told him he felt like an alien in the land of his birth. “You say I have got a homeland, but still I repeat that I am without it,” says Ambedkar. “How can I call this land my own homeland and this religion my own wherein we are treated worse than cats and dogs, wherein we cannot get water to drink?”

Since Ambedkar, other Dalits have continued to express their experience of being dehumanized, repeatedly characterizing it as one of being treated like animals by their fellow human beings.

In 1935, Mulk Raj Anand published his first novel, Untouchable. The book describes a day in the life of Bakha, a latrine cleaner, and his experience being treated as Untouchable.

In one scene in the novel, Bakha is walking down a street, care-free and head in the clouds. He accidentally bumps into an upper-caste man in the street. The man recoils, furious, shouting, “Now I will have to go and take a bath to purify myself.” Screaming at Bakha, the “touched man” yells, “Keep to the side of the road, you low-caste vermin…. You swine, you dog…. Dirty dog! Son of a bitch! The offspring of a pig!” What was Bakha’s real crime? According to the “touched man,” Bakha “walked like a Lat Sahib…. As if he owned the whole street!”

In 1949, as representatives from around the Indian subcontinent gathered at the Constituent Assembly to formulate a constitution for the newly independent nation, Dalit leader Hemachandra Khandekar stepped forward to proclaim, “Seven crores [that is, 70 million] of the people of this country have been treated or are being treated like dogs and cats by their caste Hindu brethren.” Another Dalit leader, V. I. Muniswamy Pillay, noted, “At one time dogs and swine might enter the sacred precincts of temples but the shadow of an untouchable was considered a great abomination.”

In independent India, the struggle for human dignity continues while the narrated experiences of dehumanization remain the same.

In 1992 in the book Poisoned Bread, Dalit activist Arjun Dangle summarizes the experience of the outcastes, writing, “Treated like animals, they lived apart from the village, and had to accept leftovers from the higher caste people in return for their endless toil.”

In 2002, Dalit politician Udit Raj argued, “Hinduism theoretically justifies discrimination. Dalits are treated worse than animals, dogs, snakes…. What’s the point in remaining with a religion where an animal is more important than a human being?

In 2014, renowned Dalit activist Milind Eknath Awad described a similar experience, saying, “Stones have value, animals have value, but humans don’t. Even cats and dogs are treated better than Dalits in our society. Humans are not treated like humans, rest all are gods.”

In 2015, Fr. Ajaya Kumar Singh, a Catholic priest from a Dalit background, compared the treatment of low-caste Christians to Hitler’s treatment of Jews, saying, “They’re treated worse than dogs.”

In 2016, a group called Akhil Bharatiya Dalit Muslim Mahasangha (ABDMM) held a protest in New Delhi. Led by Suresh Kanojea, a Dalit politician, the ABDMM brought pet dogs on leashes to their protest to illustrate their point. Suresh stated, “The value of a Dalit and a Muslim life has come to such a low that dogs seem to be in a better position than these two communities.”

As Ambedkar. asked,

“How long shall we continue to live this life of contradictions?

“How long shall we continue to deny equality in our social and economic life?

“If we continue to deny it for long, we will do so only by putting our political democracy in peril. We must remove this contradiction at the earliest possible moment or else those who suffer from inequality will blow up the structure of political democracy.”

Those who suffer are beginning to push back.

In January 2016, University of Hyderabad student Rohith Vemula committed suicide. He was working with the Ambedkar Students Association when the university suspended him for participating in a peaceful protest. Crushed, he hung himself. In his suicide note, he denounced the dehumanizing system, writing,

“The value of a man was reduced to his immediate identity and nearest possibility. To a vote. To a number. To a thing. Never was a man treated as a mind. As a glorious thing.”

Rohith’s suicide prompted a wave of international protests. “There are hundreds of Rohiths in India,” warned protestors. “There has been a longtime struggle of keeping Dalits away from the halls of higher learning.”

In February 2016, students at Jawaharlal Nehru University staged a rally. Student Union President Kanhaiya Kumar was arrested for sedition — charged under a colonial-era law. His arrest provoked weeks of international rallies which highlighted the oppression of minorities. After his release, Kumar gave a speech on the JNU campus demanding “Freedom from hunger, poverty, and the caste system.”

In July 2016, four Dalits were accused of killing cows. They were seized, stripped, tied to a car, beaten with sticks and iron pipes — on video — and marched for miles to the city of Una, Gujarat. The video went viral and provoked months of protests by thousands of Dalits in Gujarat.

Jignesh Mevani emerged as a leader of the protests.

The Una flogging galvanized the Dalit community, inspiring them to greater rigor in the struggle for human dignity. It played a significant role in Gujarat state elections in December 2017 and Jignesh Mevani was elected as a Member of the Legislative Assembly.

Calling for national change, Mevani slammed the ruling party — the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party. “I want the BJP to lose as they follow ideologies of Mussolini and Hitler,” he said. He pointed to Ambedkar’s legacy, talking about “the Babasaheb who wanted to end Brahmanvad and Manuvad.”

In January 2018, Dalits gathered in Maharashtra to commemorate the battle of Bhima Koregaon — a victory of outcaste Mahars over high-caste Brahmans. The rally degenerated into violence when Hindu nationalists attacked the Dalit gathering.

What was so objectionable about the gathering? Rahul Sonpimple offers some insight. Rahul, the son of a Delhi rickshaw puller, is a member of BAPSA — the Birsa Ambedkar Phule Students Association. Rahul explains, “Acknowledging and remembering this battle… actually runs counter to the normative aspect of the caste system, which does not allow space to a Dalit to act as a militant.”

In other words, the upper-castes feared that Dalits were acquiring a sense of pride, dignity, and self-respect. They feared that Dalits were beginning to assert their humanity. So the upper-castes felt compelled to beat the Dalits down.

Yet the Dalit communities of India refuse to be beaten down. They are hungering for a final end to their centuries upon centuries of oppression. They are standing up and speaking out, which is the only path to freedom. As Rahul explains, “Oppression will not end unless the oppressed sections rise and raise their voices.”

In April — this month — the struggle against oppression expanded as communities all across northern India called a Bharat Bandh. In Punjab, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, Gujarat, Maharashtra, Rajasthan, Bihar, and Jharkhand, hundreds of thousands of Dalits rose up in synchronized protest. And they did it on their own — without a political party.

One of the organizers of the Bharat Bandh is Ashok Bharti, who is the chairman of the National Confederation of Dalit Organizations. “A new crop of grounded, firebrand leaders have just taken over the Dalit community,” says Bharti. Furthermore, he declares, “No political party in this country, BJP or Congress or BSP, has the slightest clue about the sort of resentment brewing among Dalits in the country right now.”

These firebrand Dalit leaders are setting brushfires of freedom in the minds of the oppressed men and women of India. They face many challenges, but every spark they strike stands to spread like wildfire. The flickering flames of liberty may yet become a raging conflagration which melts the chains of the oppressed.

The civil rights movement is surging forward. Dalits are chanting, “We are 100% human.” They are doing more, however. They are not just declaring their humanity, but stepping forward and seizing their humanity. The battle to secure their human dignity has grown red hot.

Dr. Bhim Rao Ambedkar was born on April 14, 1891. He insisted that no reform or adjustment or adaptation or amendment or refinement would ever alter the reality that the caste system is, at its very core and by design, a system of dehumanization. Thus, he demanded the annihilation of the caste system.

Pastor Dietrich Bonhoeffer was executed on April 9, 1945. He similarly demanded revolutionary change, writing, “We are not to simply bandage the wounds of victims beneath the wheels of injustice — we are to drive a spoke into the wheel itself.”

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated on April 4, 1968. To paraphrase some of his most famous words, “I have a dream that one day even the country of India, a nation sweltering with the heat of injustice, sweltering with the heat of oppression, will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice.”

Thank you. Jai Bhim.

Now , we are inoti a “DO or DIE ” situation.Forgetting all other differences amongst ourselves , we have to extend our unstinted and unilateral support to Muslims and Christians contesting the ensuing elections who fight the elections as independants and on other party tickets , other than BJP and Congress. Let us first save the constitution .Ambedkar said ” Educate , Organise & Agitate “. To some extent , we are all educated. What is badly missing is organising ourselves under one roof and agitating effectively. In recent times , I am able to notice that we are organising and agitating effectively. This is to be sustained . Jai Bhim.