Caste – A Personal Perspective

The article below was originally published in 1994 in Blackwell Publishers/Sociological Review UK titled Contextualising Caste: Post-Dumontian Approaches, edited by Mary Searle-Chatterjee and Ursula Sharma. The Postscript is an attempt by the author to bring the article up to date.

Abstract

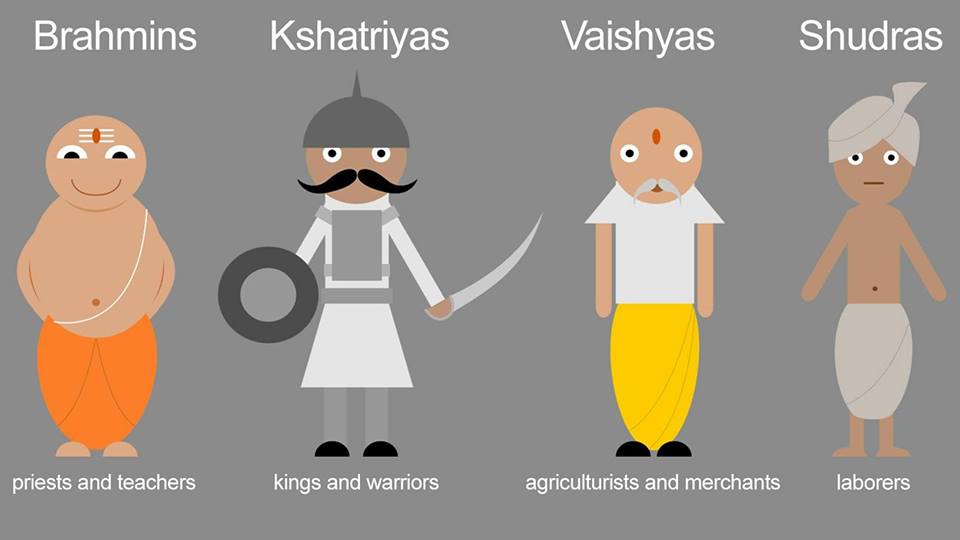

The author, a member of the Dalit caste of Chamars, describes and analyses his own experience of caste. He recalls that his sense of his own low caste-identity was impressed upon him from an early age especially at school. Yet the practice of the high castes was not always consistent and inflexible-a low caste person who has influence or whose skills are sought might be offered hypocritical respect, in any case, the high caste view of the low castes is not internalised by the latter, especially those. who have been influenced by the modern Dalit movement. Caste consciousness and behaviour pervades all communities in India in some form; it is not a monopoly of Hindus.

When the author came to Britain at an early age he was initially more concerned by the effects of racism, but soon found that casteism was as strong among Indians living inBritain as in India. This is not always made explicit, but most Asian organisations are in fact caste-based, If anything, this casteism is stronger than it was in the early days of Indian settlement in Britain when migrants were more inclined to share facilities with each other. Even those who did not practise caste openly effectively support the institutions by marginalising the issue of caste intellectually and politically. The only explanatory model which can make sense of the contradictions in Indian society is a model of, groups with conflicting interests which however survives because of the capacity of the thin cement of Brahmanism to hide the rifts in the structure.

A Personal Perspective

Caste is a complex phenomenon; this much is agreed by students of the, caste system. There are many tools available for analysing caste; economic, social, political, religious, anthropological etc. or a combination of any of these. The writer lacks formal qualifications in any of the above fields. However, my interest in the caste system goes back some twenty odd years. Having had a personal involvement in the debate raging about the caste system; I feel that I have something to contribute to the understanding of some aspects of the caste system. But first some details of my background.

I hail from the Ravidasi community, commonly referred to by the so-called high caste Hindus and Sikhs as Chamars.1 I say ‘so-called’ since no Dalit and I have met them from all parts of India, remotely thinks that the others are superior to them. They may envy the others their wealth, education etc. but I have yet to come across a Dalit who thinks that people are born superior and inferior. Many of them may believe in the karma theory but not in the Brahmanical sense. It is not the Dalits who have belief in the concept of untouchability, it is the high castes have this problem.

For me it is a question of identity. We Dalits are an ‘invisible’ community, not only’ in India but also in the UK. The non-Dalits tend to be dominant here also and these, are the people who tend monopolise all the jobs that require interfacing with, the host English community. Hence a plethora of books have been produced dealing with the Hindus, the Sikhs and the Muslims, but on Dalits, both here and in India, there is painfully little. Everything in books both here and in India’ tends to deny the history and the identity of Dalit people. Most scholars dealing the caste issues also tend to take the explanations offered by the upper Indians at their face value, ie there is no, caste amongst the Sikhs or the Muslims, caste does not exist in the UK etc. To my knowledge very few anthropologists, have really taken up the question, of how the thinking section of the Dalit community perceives itself.

The earliest I had to deal with the identity question was at the age high school at the age of 11. The declaration of religion the school’s paperwork led the Brahmin teacher to ask if Adi Dharam meant Adharam (meaning no religion) or Adi Dharammeaning Ancient Religion). The Brahmin teacher more than anyone else must have known and appreciated what AdiDharammeant. After all, Brahminism is only a veneer, at times a thick one at that, on top of the ancient beliefs and practices. In the village school, this amounted to casteist baiting. I found this to be chiding and very offensive. Even at this early age I could have answered back but decided that it would be too risky at this point. Not being able to answer back and out of frustration I lost my native Indian absolute faith in teachers and acquired a belief in myself. I consider this a lucky, coincidence. If it had not happened I might never have lost my naive Indian belief in teachers in general and thus acquire a belief in myself.

From a very early’ age I began to realise that the rules of caste and untouchability etc were not static but pliable. It was dependent on who was applying it in what situation. For example, both my father and one of my uncles faced untouchability problem at school. Both had to sit separately from the class, often outside of the classroom. However, once they obtained their qualifications and obtained jobs their high caste contemporaries started to treat them as normal. The justification was that their house was very clean. This I felt was only an excuse for many people to obtain my father’s services as someone who not only could read and write three Indian languages but also English. I was also to find out that the rules of untouchability were complex and hypocritical. There were wells in my own village and in other villages whereas a Dalit you could not get water to drink. I still remember one household, one of whose members had refused to let me drink water from their water-pot during the harvest season. However, a few years later the same family sought my help in tutoring on their sons with his studies. On this occasion, I was fed like a honoured guest. Lest; there is some doubt in reader’s mind about the way the high castes justify the practice of untouchability let me provide a further example. One of our distant relatives who was a wandering minstrel a professional singer. l was allowed to accompany him in one of his tours of the adjoining villages. What stuck in my mind was that we, as members of one of the most polluting castes around, were treated as if we were royalty. Our presence brought prestige to the household we were staying at. Indeed my ‘uncle’ had to be very diplomatic in turning down the invitations, as he was unwittingly put in a situation where he could decide who the most prestigious family in the village was.

Many such incidents made me realise that most of what the high castes said about the practice of caste system was untrue. I never believed theJats4one of land owning castes were any better fighters or braver than the Chamars as the Jats had often asserted. It was a matter of time and place. My subsequent experiences were to prove that I was right. I was to find much later the part played by Dalits in the development of such militant religions as Sikhism and the Satnami movement. I found it difficult to believe that the high castes could be genetically or otherwise educationally superior to us as I was the brightest in my class. As for their supposed posed intellectual superiority, I find it rather amusing. It is no co-incidence that Hindu society did not produce a Voltaire-like figure.

Lest I create an impression that I somehow developed these ideas on my own, I have to confess that both my maternal grandfather and my maternal uncle helped me to see things in a certain way. Both of these men were very radical for their day. Without their support, I doubt if I could ever have become the person I am. They had the experience of Adi Dharam and Ambedkar’s5movement behind them. One of the things that I noticed later on in my life was that both of these movements, very important in the North Indian setting, were more or less completely ignored by the western scholars. This is not surprising as these writers hardly ever address the future of India in serious terms. The future of India and the future of the Dalits is inter-inked.

My second recollection of identity formation is the time my family moved to Bootan Mandi, a Dalit suburb of Jalandhar city. I did not grasp the significance of Bootan Mandi till I came to the UK and studied the history of the Ravidasi community. In the early 1930s and 1940s this was the centre of the Adi Dharam movement and later, in the ’60s and ’70s, of Ambedkarism in the Punjab. People whose business mainly involved leather work6, were nevertheless, comparatively speaking, fairly well off. Not only that but I found that in the city environment it was difficult for people to subject you to overt casteism. Furthermore, in the village school I was exposed to Sikhism but in the city where the Hindus predominated, I had the chance to learn about their religion. There were people in Bootan Mandi who belonged to the Radha Soami7 sect and there were other suburbs where Muslims predominated. I was lucky enough to be exposed to all these places, otherwise, I feel that like most people brought up in India I too would have developed a tunnel vision of convenience and hypocrisy. But more than anything, Ambedkarism taught me to question everything. I have sometimes pondered on the question of why did not more people in my community turn out like me. The answer, it seems to me, is a combination of factors. My maternal grandfather’s family was comfortably well off. The family, although untouchables, owned a village shop! In fact, my maternal grandfather owned a number of shops. We would be mildly amused at times at my mother’s recollections of how the high caste customers would leave the money at the door and take the goods left there.

On my father’s side, he and one of his brothers did manage to go as far as the tenth grade. This was something of an achievement for them, as they had to sit outside the classroom. My father’s best friend of life, whilst recounting old times, would not spare even the Muslims. ‘They would invite me to their weddings etc. because I could sing the Koran beautifully, but I would be told to sit away from the others, when it came to eating, I had to sit separately was his frequent lament. He could forgive the Hindus, and the Sikhs; who were after all ex-Hindus, but the Muslims became the object of his pity. He should not have felt like this. Caste is not a unique Hindu phenomenon, it is part of Indian society, Hindu, Muslim or Christian. In this sense, it acts like a class cutting across religious boundaries. Besides, most of the Indian Muslims are ex-Hindu converts anyway.

I was born in Poona, in Maharashtra state, but of Punjabi parents. Having been born in Poona is a good talking point when meeting educated Indians. I was given a Sikh name by my father who perhaps feIt that it would be advantageous not to be openly known as a Dalit. In this he was absolutely right. When young I also had OM8tattooed on my right hand for a bet, without realising that this too could unwittingly allow me to pass off as a so-called high caste Hindu. These factors in themselves are minor. A keen knowledge of both Hindu and Sikh folklore has. proved indispensable to gain confidence in a number of situations. The knowledge of the former I acquired from a number of sources, from my maternal uncle’s town, where the Hindus were in the majority, and from another large town where novels and books could be hired for the day, which I could afford since my father was in England. From the stay in my father’s village and attending a Sikh high school I was exposed to Sikhism which I found very attractive since by this time both my father and my older brother had left for the UK and this created a vacuum in my life. Not having a mentor, I found that I could indulge myself in acquiring as much knowledge as possible. But the problem of knowledge also created another problem. How was I able to explain the internal fantastic contradictions of Hinduism and the day-to-day behaviour of the ‘caste free’ Jat Sikhs? While I was living in a large town, which was the centre of activities of the Republican Party of India, two aspects must have had a significant influence on me. One was the campaign by the Republic Party of India, in which both my mother and I attended demonstrations where people willingly courted arrests. This exposed me to Ambedkarism. Secondly, I came across a holy man named Lal Bawa who was to undertake a fast unto death which was later called off, by the request of the RPI leadership. In my later experiences, I came to realise that there was no artificial Chinese wall between caste, politics and religion in India.

In the school in the UK I found no real casteist behaviour. We were all too busy defending ourselves against the racist taunts of the white boys. Things are actually worse these days, I am informed by the Dalit children. Born and brought up in the UK, many of them find casteist insults very emotionally disturbing. In the UK I undertook an engineering apprenticeship in the foundries of the West Midlands. This proved to be another eye-opener. Caste feelings were very strong with the best jobs being zealously monopolised by the Punjabi Jats. Being a technical apprentice I was an outsider, presumed a Jat by other Jats. This gave me a chance to study the caste conflict in the British climate. In and out of the factory the castes are separated, each caste having its own place of worship. This was not always so. In the ’50s and ’60s people of different castes shared houses, cooked for each other, even shared the same bed under a rota system. This however changed when the womenfolk started to arrive from India and the system reproduced itself with some interesting variations, tailored to British conditions.

It is a truism that an outsider cannot really know, the inside story. However, the outsider does possess some degree of objectivity although this itself may be conditioned by his or her background. In this the non-Indian sociologists and anthropologists are better than their counterparts. There is no substitute for first-hand experience, however. An English friend of mine, who was joining his PhD thesis in India, unwittingly found himself ‘excommunicated’ and treated like an untouchable, after attending a low caste’ wedding. He confided to me that after that incident he began to look at his own work in a different light. Many thousands of miles away, ten years later, I found that the wife of a ‘Gujarati friend of mine will not drink water or eat food at my louse. My friend himself had in the past asked me not to declare my caste to his son or daughter either, both of whom are graduates of British universities. I had known about the practice of untouchability and caste taboos in the UK but this experience brought home to me the depth of these feelings, even in the second generation. It is a well-known fact that nearly every caste grouping has its own organisation or temple and strict caste divisions are observed when arranging marriages.

Most Asian organisations are caste based. The control exists even in community organisations up to and beyond the local council level. The degree of control exercised by these caste groups did not become clear to me till I, together with some English friends, tried to persuade the local library to stock books by Dr B.R. Ambedkar. The types of excuses used by the ‘high caste’ officials to justify refusal would be laughed at if it was a race question. Six years later we have given up the effort. That this can happen in a borough which has declared anti-racist policies is more of a revelation. Even more shocking was the revelation that a very respected journal on race did not want to know about this. It is not only the people in power who behave like this. In a research group that I belong to I have found very strong tendencies to marginalise the caste issue and sometimes to deny it altogether. Interestingly enough my English colleagues have always been very sympathetic whilst the greatest hostility has come from the supposedly caste-free Sikhs. Again, my personal experience, and that of my white English friends, of the Indian political left in the UK is that it is so riddled with casteism that it merits a study in its own right as to the reason for, the enduring power of the caste system.

AlI this is not really surprising at the· end of the day. There is no liberal tradition in India. If there are supposedly groups of people who suffer from a guilt complex, then Indian society forces people to be the polar opposite. Keen observers of Indian society may have noticed the degree of prevailing hypocrisy. They are not mistaken in this. Even writers critical of the caste system, writing for the western audience, try to portray the image of a well lubricated, co-operative and harmonious society providing peace and contentment all around. The Indian caste system is viewed by the Dalits as the largest Apartheid system in the world. Indian intellectuals both in India and the UK have found that the best policy of defence is attack. Hence, silence, denial, justification and many times downright dishonesty are resorted to. Four years ago, I had a chance to talk to the cast of a famous drama group who had performed a play about the untouchables in ancient India. It came as somewhat of a shock to me that they saw the play in terms of anti-racist work, to illustrate racism in British society. They did not think that there was any caste problem in the UK or indeed in India. This group has credentials as the Indian left drama group in this country.

In the UK, I was to realise that most of the things that I had read about caste did not seem to fit with the reality as I had experienced it. Secular countries such as the UK ought not to be able to sustain caste, but here it was in some ways stronger than in India. This is the feeling of many visitors that I have come across from India.

Much later I was to find out that it was not what the books told you that was important. It was the contradictions in the arguments that were more important. There was a whole range of subjects which did not make sense if one went by the Brahmanical or sociological explanation of things. The low caste people appeared not to have any history at all. Yet there was no need to invent one. It was there all right, and there was no need to throw away everything and start from scratch. In some instances, it merely needed a critical approach but in others the truth had to be stood on its head. A functional, a structural approach was the least effective way of approaching the issue. A model of groups with conflicting interests is the only model I know which can explain all the. peculiarities of the caste system. The caste system is supposedly an Aryan invention, and yet the Aryans went to other countries9 without reproducing this system there. The cause must, therefore, be uniquely Indian. Race, dis-credited as a concept in anthropology, is another red herring that is sometimes used to explain the caste system. Black Brahmins and fair skinned untouchables are not uncommon. What is more important is that the history of Brahmins is only a fraction of the history of India and at times it is distorted history. What they call history is a veneer on top of the development of the Indian history and culture. What is underneath is the real thing.

The best way to view the caste system is to view Indian society as a flexible matrix, a sort of invisible ether in which the economic, social, religious, and increasingly political forces can influence the society without causing rupture of the basic fabric of society. That is not to say that minor ruptures and scars are not there. These have been repaired so skilfully that it is difficult to say if there has been any damage to the mosaic. Only a close critical viewing will reveal the thin cement known as Brahmanism and this too has changed over the years!

Will I stop ‘passing’ myself and one day declare what I am, for example in my office? The answer must be a definitive no. From my bitter experience and that of my friends, I know what happens when people find out about your caste. I know it is the society which is to blame, but for me, I have only one life to live. I must choose my own battleground for struggle and it is not the workplace, at least not in the UK. Besides passing myself of as someone else allows me to be a ‘fly on the wall’ in the Asian community and understand it much better than any other ‘outsider’.

I look to the future with apprehension for my two-year-old son. In this, I am perhaps no different from other Asians in the UK who face similar problems. But there is a crucial difference. My community, according to the socialists and sociologists alike, does not even exist. There are Hindus, Sikhs, Jains but no Dalits. There are no textbooks on the history, tradition, culture etc. of my community. People have neither time nor education to write books that require such Herculean effort. From my personal experiences, I know that my son will face a similar if not worse kind of casteism, more confusing and hence psychologically more insidious. He may decide to drop out of the Indian culture altogether if he gets disgusted with it beyond limits. That would be a pity as above the stinking Indian society lies the lotus flower of an alternative tradition which is comparable with the best in the world. My next main project will have to be to write the history of the Dalit people for the ordinary public.

Post-Script

Since I first wrote this article, nearly a quarter of a century ago, there have been some changes, some for the better but some others for the worse. In 1980s, together with an influential English friend, I met a couple of journalist from the BBC with a view to making a documentary about caste discrimination both in India and in the UK. Despite a two-hour discussion in a pub and my strong pleadings, we were very nicely and almost apologetically told that there would be no public demand for such a film. These days such documentary are fairly common. Even the subject of caste discrimination in the UK now makes a regular appearance on TV and on the radio. The word Dalit seem to be fairly well-known even to the young black woman behind the counter at my local bank.

Universities used to have student societies which were based on nationalities eg India Society. These days religious identity politics have come to the forefront with proliferation of Hindu, Sikh and Muslim societies leaving little space if any for Dalit students. Then it was not uncommon for a Muslim fellow student to be invited to a Hindu Gujarati Garbha dance. These days if a boy or especially a girl is foolish enough to invite her young Muslim acquaintance and he the latter is foolish enough to accept it, chances are that the Muslim boy will be roughed up in the car park thus sending a clear message to other boys to stay away. BMW does not stand for the make of a German car manufacturer. This is the acronym for an unsuitable marriage partner for their children dreaded by all upper caste Hindus. It stands for Black, Muslim, and White. Whereas White can be grudgingly accepted, at least in public, it would take a brave soul to accept a Dalit son-in-law although there have been rare exceptions.

People from the left who could never be prodded to do something about caste both in India and here, now seem to be jumping on every anti-caste bandwagon that they can find. One might be forgiven for thinking that they and not Dalit men and especially women who had brought this change about.

A new book on the immigrants’ experience provides a dozen or so life examples but the editors could not find a single Dalit to narrate his or her experience, so this was done via proxy by a Muslim woman!

Hindutva was always present in the UK but at low levels. It now comes in aggressive and hydra headed manifestation. Politicians in the next borough have openly called upon the Hindus to vote for a candidate who opposes anti-caste discrimination legislation measures. My local library recently celebrated Ganesha as a ‘cultural’ icon for nearly two weeks. An exhibition on dozens of books on Hinduism shows caste either airbrushed out altogether or seen via a soft focus lens and portrays Adivasis as ‘demons’, ‘monsters’ and other undesirable beings. My local park has Adivasis exhibited as ‘exotic’ Indian dancers organised by front companies and organisations who work hand in glove with some of the biggest looters and polluters of Adivasi lands.

The local libraries have one title which contains excerpts from Dr B R Ambedkar’s writings, reproduced from freely available internet resources. DhanjayKeer’s biography has made it to the shelves and so have two copies of Arundhati Roy’s The Doctor and the Saint which has been heavily criticised in India by many Dalit activists and intellectuals. There is one title in Hindi by an obscure writer.These titles are spread amongst a number of different libraries. The library has therefore met its diversity criteria, according to the young black librarian who is probably too afraid to do anything about it on the pain of losing her job because she probably has an upper caste supervisor.

A year prior to the matter of library books, I offered to give a free talk in one of the lecture room, which is supposed to be available to anyone wishing to give a talk on any subject relevant to the community at large. Great difficulties were put in my way. I succeeded after many months but not before I was asked to provide a copy of my presentation a couple of weeks prior to my presentation. I asked in writing whether everyone who gave a talk was required or asked to provide an advanced copy. I did not get a reply to my question.

The British government is making a show of passing an anti-caste discrimination legislation but it will be so watered down that it will be completely ineffective in practice. The government is always open for business with anyone from Kazakhstan to Saudi Arabia to India and this negates much of the lobbying by any human rights organisation. Ambedkar himself was scathing in his attack on the British for not tackling untouchability and caste oppression in colonial India, so there are no surprises here in the 21st century. Caste discrimination has always been insidious and fairly well institutionalised. It is more so now because although one can see some doctors, lawyers, accountants and social workers who are Dalits but the majority of Dalits still find an uphill struggle to make it in a world dominated by the upper castes who interface with white middle-class men in power. Caste discrimination starts very early these days; the fight to get your child into a decent school and then into a reasonable job or the university and also their entrance into a suitable internship. The most dangerous form of caste discrimination is the type where it comes combined with racial discrimination and also sometimes with gender discrimination. Token upper caste men and women in power are much more damaging than any racist person because they normally work hand in glove with dominant white people behind the scenes. It can sometimes be heartbreaking to see a brilliant child nearly destroyed by institutionalised casteism acting in a toxic combination with racism.Casteist bullying is more or less normal in schools dominated by children with SouthAsian roots. Casteism operates from the level of a school governor and a supervisor in a factory or in a professional environment to a carer for the elderly.

These days, in many instances, I no longer bother to ‘pass’ myself as someone else but having done so for a number of years it has given me an insight which is priceless.Both of my children have had first and second-hand nasty experiences of the caste system, so I no longer need to explain to them about their background. I am still hoping to finish off the Herculean task that I undertook many decades ago.I have yet to meet any apologist of the caste systemwho can defeat me in a debate on the Indian caste system regardless of their background or academic achievements, so there is still hope for me.

Notes –

- A pan-North Indian caste of leather workers. The word Chamar is about as offensive as the word ‘Nigger’.

- Literally, means ‘oppressed’ -a word most so-called low-caste people like to use to describe themselves as it conveys a more universal and defiant meaning.

- A Punjabi socio-political self-respect movement of this century whose basic purpose was to fight for the human rights of the so-called untouchable.

- Mostly Sikh landlords or rich peasants -the major dominant caste Punjab countryside.

- Dr B.R. Ambedkar, the first law minister of independent India known twentieth century Dalit leader. Ambedkarism is the core of Indian Dalit philosophy.

- Considered ritually highly polluting by Hindu tradition.

- A sect whose members profess the teachings of North Indian Bhaktas and the Sikh Gurus. The members are keen on vegetarianism and are theoretically anti-caste. The reality is somewhat different as the sect in reality is a Rotary Club for the upwardly mobile people of all castes.

- A sacred Hindu utterance.

- For example, the Romans, Greeks, Slavs, Teutons and Hittites all have Aryan roots.

Author – A Shukra (pseudonym)

© The Author retains the moral and ethical copyright of this article. Please contact the Author via website for translating this article into another language.

+ There are no comments

Add yours